Taking a horse to water | September 2023

Hello, and here’s our third outing.

It’s getting both easier and harder – there’s always more art and art-adjacent stuff out there than I can possibly get to. Some exhibitions are really blink-and-you’ll-miss-it, and I certainly do miss things. Sorry. Also, it's a bit slower coming to you this month. I had cold.

But here we are. Hello.

Make and Do Recommends

Stuff I think is excellent

Of the current crop of things on, I suggest that Jane Giblin’s Dear Kate: The vision of the Mitchell women at The Allport Library and Museum of Fine Art is an essential visit. Partly because Jane is a go-to artist for me. Partly because of the consistency of the shows that the Allport puts on – I want to pay a bit of homage to the Allport itself: it’s one of the best spaces we have in the south, with a consistent high standard of curation and a commitment to bringing pertinent material to light. There’s a very strong commitment to women artists over the years, palawa artists get a look in, and there’s been some excellent excavating of the Allport Collection. I’ve found I get a kick from well-crafted archival dives: I’m fascinated by ordinary people and how they managed their lives (far more than I am by the indulgences of the rich and powerful). There’s a flickr account that documents exhibitions reaching back ten years (have a look at that here). The Allport is excellent: their exhibitions are on for ages (but time does run out so get in there), there’s a great kids activity room just next to it, if you’re super keen there are excellent talks associated with exhibitions, and just about everything is free.

The Listening Room was an absolutely magical radio program I used to tune into years ago. It’s something of a high tide mark for radio of an experimental variety in Australia, and if you want to get your ears and mind expanded this is a fantastic place to start. I found out a number of the shows were archived on BandCamp, and when I’ve been able, I’ve been picking away at these – you can buy them for a pittance, or just stream them, and get an excellent view into the possibilities of radio.

The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction is an essay by Ursula Kroeger Le Guin, who is probably one of the writers I most adore. Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea, a book which would probably be known as Young Adult fiction now, seized my nascent imagination at about the age of ten and has never left me. She’s very consistent, both in her fiction and her ideas. I acquired a tiny, beautiful edition of this essay from 1988, published by Ignota with an introduction by the great Donna Haraway, which is also a fantastic read. The basic idea here that the container – or bag – was a far more useful and important tool in the story of human evolution than the spear, and that by understanding that we may arrive at a very different understanding of history and storytelling.

All Art is Ecological is an essay by Timothy Morton that delves into what it’s like living in an age of mass extinction. It’s quite heavy but also kind of irreverent – Timothy is a philosopher but he writes in an accessible, even fun tone that’s great to read. This is my first introduction to Timothy Morton, but it’s whetted my interest: their take on ecological thought is incredibly refreshing, and I want to read more.

Okay! Do enjoy the offerings for issue three, do give us feedback, and please do send Make and Do along to anyone who you think could be interested.

Do note, we’re also looking for ideas to examine for a series on the Make and Do podcast: do you have a question or topic to do with arts and culture you’d like to see us take on in fun report form? Tell us.

Thanks for your support,

Andrew

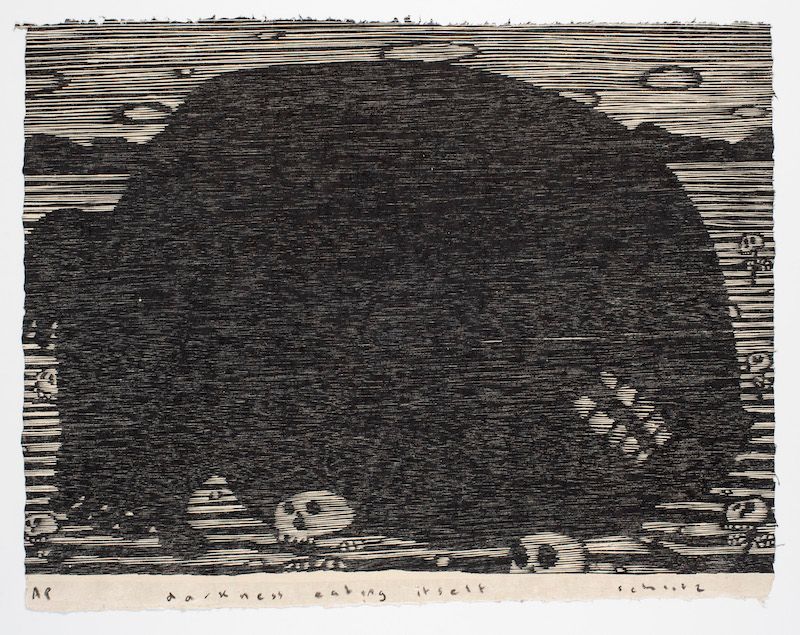

MICHAEL SCHLITZ: The Well in The Waterhole

Bett Gallery, 1 – 23 September 2023

Michael Schlitz is a bit different. I find myself genuinely excited when I realise a show of his is up or even on the horizon, and this is because I know and do not know what it is I’m going to see. Schlitz has a defined look to his work, and it’s amazing because it’s strongly stylised and doesn’t look like anything much else, although it reminds me most of two things: underground comic book art, and folk art or sculpture.

I’ll pull this apart a bit for you: comics are my touchstone. Comics are where I came to art, how I fell in love with art, and where I go to hide when art becomes a bit too much for me, which it does, particularly after seeing a really huge, bombastic, intense Exhibition of Large And Important Art. These shows are great, but because I like comics, I like intimacy. Comics are things one holds, that one looks at closely, that one peruses and engages with over and over again, sifting out the secret meanings from. I began with obvious comics from mass market commercial entities, like the house of mouse and the manspider, alongside the astonishing churn of comics from the UK that came out weekly (weekly! Hey artist, produce 4-5 pages of comic art a week. Do that every week for a year), where I found the weirder and more kinetic art, and politics[1]. This led me to underground comics eventually, with even weirder art that was often astonishingly complex, intense and worked. I even recall seeing comics done entirely in woodblock printing[2]. What this dripfed into my mind was a love of resolutely singular, different art that hovered at the intersections of a Venn diagram of weirdness, the grotesque and the lush.

I see some of this in the art Michael Schlitz makes, and it’s a huge reason why I like it: there’s a pulsing familiarity there, not some much in the work, but in the parallels with the art that made me.

Alongside this outside source there’s an influence from art from first nations the world over: Schlitz is pretty clearly informed by art traditions that stretch back far into time; certain forms and images appear again and again, which may be simply how Schlitz makes images, or it may be an intentional move to create a kind of visual lexicon, or it might be both, or neither. It does seem clear that Schlitz has done some research into art made outside the art world, outside the first world, and outside the art market. Schlitz’s work does feel incredibly hands-on and intensive: he uses simple tools and works everything quite intensely; when you look at Schlitz piece, you’re seeing not just the figure but an intense background that is worked so much it’s filled with movement and marks. There’s a lot of textural density, which makes every single image feel like it was cultivated rather than made.

This leads me to a nebulous and potentially esoteric reading of Schlitz’ work, but I’m going to tease this out: Sometimes I think that Schlitz drifted out into the dense bush near his dwelling, and dug up, or saw high in the trees, or caught a glimpse of across a stream, what and who he depicts in his work. Each work feels like it was grown rather created, and that Schlitz plants seeds and patiently, meticulously cultivates.

Schlitz is one of those artists who feels like a conduit through whom art flows from another space entirely. I imagine him working, making his repetitive marks, the action of which induces a trance-like state of focus. Images come, are drawn onto the surface and this timber is carved with hand tools. Layers are created, and there’s something about this carved stratum that adds to the feeling of ancient fragments of knowledge that’s so consistent in Schlitz’ art: it always feels old.

But it also feels prescient.

One image, the Denier, really caught me. This depicts a figure seated in front of a dramatic screed of boulders. Scattered on the ground are fragments of shells, plants. We are perhaps near to the sea, and there is horror: eyes float in the sky, watching, accusing. The figure appears to be covering its ears and its head and body are a terrifying black blob: nihilism and horror are implied. We do not know what it is that is being denied, but my mind went straight to climate breakdown, to biodiversity loss, to mass extinction. It could be a more personal denial, but then we would not have the actual assignation; we’d say that the person was in denial. No, it seems bigger than that, an allegory at its maximum potential.

Despite the ancient trappings and hints of deep and long time, perhaps Schlitz is making a mythology of now, that will be devoured by someone, or something, far from now. It is night impossible to avoid at least the potential for myth and lore into Schlitz’s work, and perhaps that shouldn’t be an issue anyway. Perhaps we could ask who is it for, these dark and shining fables, and wonder if it is for us in the now, or for the denizens of the devastated and terrifying future to come.

[1] This is a digression, but I’m struck now but how much some of the comics I read as an under ten were filled with anti-war polemics (in particular, Charley’s War, the story of a boy who faked his age to enter the trenches and was absolutely horrific and deglamorized), humans portrayed as villains (and even colonialists), some strong women characters, parodies of fascism and general anarchy.

[2] I’m going to have to write something lengthy about comics and art, and how problematic and glorious comics can be.

INTERFACIAL INTIMACIES

Bruno Booth, Amrita Hepi, Léuli Eshrāghi, Bhenji Ra, Aleks Danko, Cassie Sullivan, Georgia Morgan, Cigdem Aydemir, David Rosetzky, and Shea Kirk.

Curator: Caine Chennatt

Plimsoll Gallery, 8 June – 5 August 2023

Identity has, somewhat disappointingly, turned into a loaded term in the ongoing culture discussion we find ourselves involved in the continuous ever present now. Or at least it was – the term ‘identity politics’ was being thrown about so much by hysterical right-wing media it seemed to lose any genuine meaning and become something of a dog whistle for the right, in much the same way that the phrase ‘politically correct’ did a while back and the way that ‘woke’ is being used at present. I find this kind of thing annoying, tedious, and dishonest.

Identity isn’t something that can easily be reduced to a bite-size media-friendly catch phrase; it is necessarily complex, and necessarily fluid: how any of us might understand ourselves is subject to change over time as we synthesize our experiences and find new contexts. I recently discovered that I’m a neurodivergent person. This has not changed my identity, but has certainly given me insight and expanded my understanding of what my identity might be, and gives me ways of looking at who I’ve been across the arc of my existence until now. It’s important information and gives me new tools to navigate with. It doesn’t provide answers: to me it points to the complexity of my personal identity, and the notion of complex influences and interactions on what my identity is, or what it might be.

Interfacial Intimacies delves into a notion of what makes an identity, but the clever aspect of the exhibition is its avoidance of the didactic. What we see is a series of fragments gleaned by the curator Caine Chennatt that exist to not form a cohesive thesis, but to ask a sequence of questions about what we might understand identity to consist of. This is a great strength of the show – it doesn’t claim definitiveness. The works themselves are a loose collection of strands of how someone might understand or express who they are, and don’t come from any particular location for a personal engagement with how someone might understand themselves. It’s not about gender or culture, and indeed we could see Interfacial Intimacies as undermining the need to present a particular identity at all – rather, what’s being suggested here is that we as living entities contain multitudes, and that this is not as fixed as the dominant cultural paradigm might want us to understand.

Identity is complex and shifts through context, perhaps. The perhaps is important here because what this exhibition is tackling is multiplicity and difference, and where identity comes from, and how that shifts around and becomes something else. If there’s a central idea I could take away from Interfacial Intimacies it’s that identity is fluid, that it’s a continuum, and that who we are is a process that keeps moving: We discover new information. We have moments of revelation and we find ourselves blended and bending. We interrogate, we see, we feel.

I realise to this point that I’ve not talked about the actual art much, but about the ideas the art gave me, because that aspect of this show is really strong: the construction and curation really feel like a narrative is being created, like a conversation is being initiated. The contents of the show are wild in themselves, and well worth experiencing. It’s hard to really pick something out, but Bruno Booth’s work Body Shots is striking: it places highly detailed visions of a disabled body in exquisite context, creating a notion of beauty that expands and undermines what we see as a beautiful body – the richness here is found in the body’s singular uniqueness. This work is incredible, presented in a striking manner, and deserves to be seen; the unique aesthetic here overturns so much.

A more elusive aspect was the performance of Bhenji Ra. This was part of the extra material Caine Chennatt blended into the overall exhibition that had aspects you would miss if you weren’t there. I was fortunate to be there as Bhenji Ra emerged like a feral hybrid being exuding sexuality and power into the gallery space and stalked through it. It was unnerving and exciting, and disruptive. It also unlocked this show for me. Caine wasn’t making a strident statement, but presenting the potential of multiplicity, and suggesting that understanding who we might be on any given day is a form of work, that presenting ourselves takes effort, and that sometimes an identity might be at odds with the dominant culture.

I think more than anything though, Interfacial Intimacies asked me to consider my own privileges and understand what people who don’t present as a white man might have to go through to just be themselves. Which is possibly not the main thesis of the exhibition, but a possible reading of a curated selection of works that encouraged the audience to mount their own interpretation. The show did not make assertions: it asked me what I thought, and then almost incidentally, asked me who I was.

It was disconcerting, in the end. Because if I’m truly honest here, I do not have a stable answer, any more than the shifting presentations of identity found in this rigorously thoughtful show offered a concrete statement – but how could it have?

Our identities shift and there’s friction, and resolving these tensions is the work of existence.

DIFFICULT TERRAIN

Emma Bugg, Janine Combes, Lola Greeno, Jane Hodgetts, Jeanette James, Shauna Mayben, Emily Snadden, Gabbee Stolp, Sarah Stubbs, Anna Weber

Rosny Schoolhouse, 1 – 24 September 2023

What is it that makes something precious? Truly precious? What is it which we infuse an object with that make sit important to us? It’s an easy answer, but also a very subjective one: when it’s a symbol of something we love, be that a person or a moment or a complex concept, that a tiny keepsake comes to symbolise. That’s easy enough to understand: the meaning grows like a subtle barnacle of memory that bulges with time. We know this, we understand it. Jewellery can be a place where memory, love and hope are stored.

These are precious things. We carry them; we give them to our children and our lovers. They outlast us, and we become part of their story. So much weight for something so slight.

To read more of this review, you can subscribe to Make and Do for a small monthly or yearly contribution. Click here to upgrade.

~ Already a paid subscriber? Your full copy will be available for you in your email inbox and on the Make and Do website. ~

Make and Do is mostly written and researched by Andrew Harper, with technical support and audio production by Pip Stafford.

Make and Do is supported in 2023 by Arts Tasmania.