Backyards of all kinds | October 2023

Hello.

It’s here and it’s dense. I need to know: is there too much writing? Do you need more? Less? More but shorter? Is 200 words enough? Sometimes I want to think more and longer about some art because of the amount of work that’s gone into it. Sometimes I want to think less about some art because of the work that’s gone into it.

Do you want more images? God, images. They’re such a pain. I was thinking I’d do a mood board for this bit but it would have probably taken longer to make than it would to write this down so here we are.

Okay.

I do want to do this, though: I’m incredibly sorry for the referendum result, and while I really can’t speak for anyone else, I extend my deep shame about this to every First Nations person across the land, on their country, speaking their truth. While I’m not sure what I might do right now, I want to keep looking at the marvellous and important art First Nations people make, and to keep telling people it’s marvellous and important. That I know I can do. In a general sense, some of the most outstanding art I’ve seen in recent years in lutruwita/Tasmania, has been created with great love and insight by palawa/pakana people, and that work has opened my eyes, made me weep, and shown me things I needed to know. The powerful and confronting Reimaging Crowther project of recent years stands out. Those works meant a lot to me – they demonstrated how much art can widen, and even initiate, conversations that can lead to change.

I’ve been doing these things:

Reading How to Blow Up A Pipeline by Andreas Malm. It’s interesting in that it advocates a form of protest against climate breakdown and all the other aspects of the poly-crisis that’s, well, destructive. It really is worth reading even if you don’t like that kind of thing just because of the information it contains, such as the polluting consequences of SUV use – which hit home again when I read this .

Dipping into John Berger – The Penguin Great Ideas series has a nice edition of Steps Towards a Small Theory of the Visible, which has some lovely shorter essays by Berger. He’s always worth a read, and his marvellous Ways of Seeing is a pretty great examination of visual art, all of which is on YouTube. If you’ve never seen it, you could do a lot worse.

Listening to podcasts when I straighten the house up: there’s a tonne here, and I do a lot of ‘current affairs’ stuff, but I’m really getting into Download This Show, hosted by Mark Fennell, who also made the almighty Stuff the British Stole, which, if you’ve not given it a whirl, is an excellent primer for the pervasiveness of colonialism that explains how a lot of what happened during the height of the British Empire is still affecting us right now.

Do get in touch about anything, particularly something you want to see a podcast about – which can be anything to do with art at all, not just art in this place.

Thanks and stay safe out there,

Andrew

Dear Kate: The Vision of the Mitchell Women

Jane Giblin

Allport Library and Museum of Fine Art

11 August - 10 November 2023

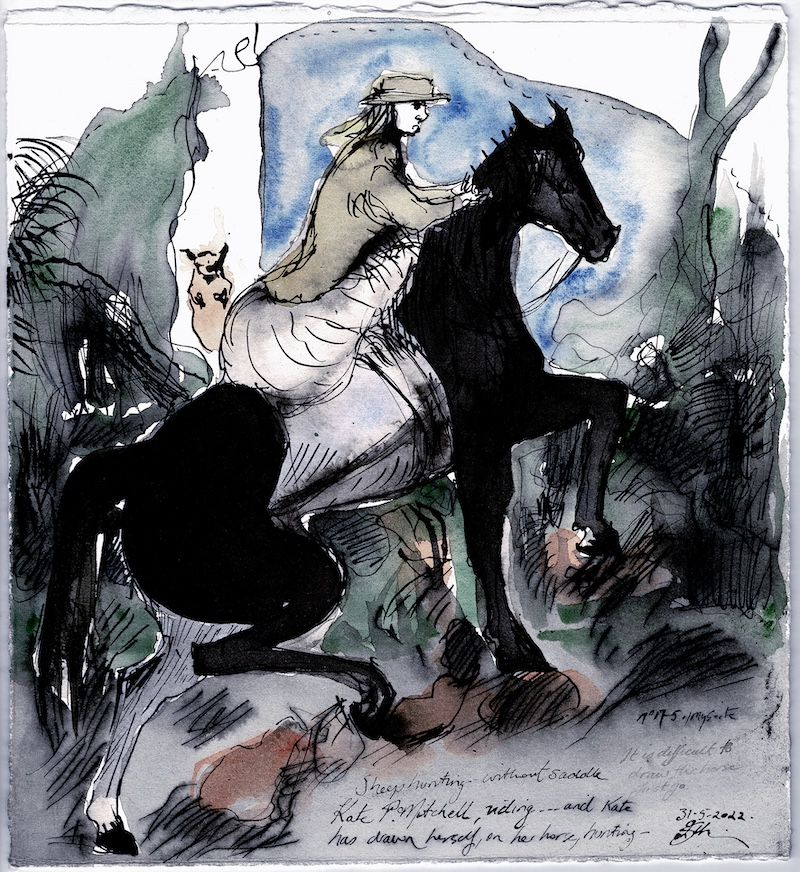

Let’s begin with animals. There’s something about the way Jane Giblin draws animals, like a horse, or a roo dog in the works of Dear Kate that just really grab me. There is a certain looseness to her line that makes the animal really alive: it’s something that moves and eats and runs. I can almost smell that dog smell when I look at the roo dog image. I can hear the rhythm of panting.

Everything Jane does has at least an element of that quality. I think it’s the sheer visceral attack of her line work that really does this, and the way I imagine all the images in Dear Kate were generated.

Giblin is no stranger to historical research and delving through archives. Her last major body of work (although there have been others since) was an investigation of one branch of her family tree that had connections to the Furneaux Islands. This new collection has similarities, in that it’s based around Giblin’s family tree, but it’s a lot more specific – it looks at three women who lived on the east coast of lutruwita: Catherine Augusta Mitchell and her daughters Catherine (Kate) Penwarne Ball, and Sarah Elizabeth Emma Mitchell. Katherine was known as Dear Kate, and she remained so named after an early death at the age of 31. As it happens, there’s a scrapbook that has survived since the 1860s, which contains drawings and paintings of and by these women, and gives a view of their existence. The book itself is incredibly fragile and precious, so Giblin has basically made a copy, and created a series of water colours and prints that extrapolate and reveal what’s been sleeping in an archive: a very different picture of the lives of women in the colonial era.

Our heroines are shown riding, boating, working with dogs and finding lost sheep. There’s an understanding of active, physically demanding working lives shown here and it’s kind of not what one thinks of when one considers the colonial era, but this is because Giblin has found a differing historical source to work with, one that is about the lives of women, as documented by them. You can see the relish with which Giblin dug into this material – producing dynamic work that is filled with movement and snippets of narrative. This kind of thing really suits how Giblin makes art – she’s all dynamism and attack in her work, so finding subject matter as lively as this is a gift and she really makes the most of it.

This might be the best thing I’ve seen from Giblin to date, combining as it does revelatory archival research with really vigorous art. Everything moves and is very, very alive.

Apparently much more is due to emerge around the Mitchell women, and there’s no doubt Giblin will produce an intense and engrossing body of work. It’s pretty much what she does as an artist, and the way in which she reveals the lives of extraordinary ordinary people remains quite crucial for art from this island.

What Remains: Fern Tree Retreat

Peter Maarseveen

Good Grief Gallery

22 Sept – 15 October

Classic analogue photography is a wet, chemical process that feels somewhat like a form of magic even if it does all follow some perfectly scientific procedures. Think about it: light is captured in a box, imprinted onto a special surface and then is given a chemical baptism so that it becomes visible. It’s very exact but it also is not; there are many ways one might interfere with this process or do it slightly differently, and even if it doesn’t work as it should, it can still produce interesting results. Some who work with photography can become just as interested in this loss of control, in surrendering to accident and experiment, as other might in exactness.

Peter Maarseveen has a foot in both camps, and in others as well. You can see his work as photography, and so it is, but that might do it a disservice, might limit what it is. There’s also a lot of conceptual investigation in the work, and a lot of poetic, implied elements, and even a notion of performative endurance: Peter does some quite intense things to get his images, that require planning and effort; and everything he produces is rolled up in a staunch DIY, re-using ethic: as much as possible, work is created with found and re-purposed materials, which adds to an overall aesthetic feel that makes the art quite distinct.

What Remains is an investigation of a ruin, the last, barely visible fragments of what was once a day hut on kunanyi. There used to be a number of these huts. Now they’re largely vanished, consumed by time and the bush’s slow reclamation. Pete found the location of one, Fern Retreat, somewhere around the Mrytle Gully region, and it’s barely recognisable: it’s little more than a dank cairn of rock. He was prompted by a family connection – his grandfather had found the hut prior in 1835, and taken a photo. Later, Peter himself found another image – a glass plate negative of two people standing in front Fern Retreat.

Coincidence and personal archaeology are mined for a connection to a lost place and another time. The site was found, and photographic images were created, using many processes and ideas: Peter works with pinhole cameras, so he took one in. He collected water and took that out, mixing it with the developing chemicals. He buried film at the site, returning after it had marinated for a time and retrieving it, an impression of the very earth taken in a direct way. He made developing fluid from plants gathered from the area, and used this to create his images of dense, living forest.

It's quite remarkable: Peter literally makes images from the elemental essence of what he photographs, mixing the procedure of photography with poetic process that has some hint of alchemy. His images are uniformly rich, and capture a dark beauty that exists at the floor of a thick forest, where it is dark and dappled with slighter light. The processes used and tweaked reflect this, and even in some ways become it; the photographs are literally made of the location.

Peter Maarseveen is quite a unique artist in some ways – he works slowly, using an extensive knowledge of photographic methods and process that he manipulates and creates new contexts for. He feeds this into research and profoundly sensitive love of a place – much of this exhibition is about the sheer amount of time spent intimately searching the forests and slopes of kunanyi; it is clear that it’s a place Peter likes to be, that he feels a connection to. This is evidenced in the success of the work: the key ingredient is that deep fascination with a place that resonates for the artist.

It’s quite incredible really: Peter Maarseveen makes magic photographs that use earth, water, the light of the sun and exposure to air in their composition. It’s not obvious but it’s there, and it’s a sterling example of the strength of a dedicated process in making art – this work is quiet and humble, rather like the artist himself, but it stands alone in its complexity and its genuine creation of deep verdant emerald wonder.

In My Backyard

Liam Ross Baker

Good Grief Studio

25 August – 17 September

There have been two shows this year from Liam Ross Baker, and I’m convinced: this is pretty damn interesting art. There’s a mixture of a kind of domestic genteelness with something mildly sinister going on: which leads to the possibility that this work is genuinely surreal. Surreal is an odd term to use in art; it’s often misunderstood and as a result, misused. The problem is that it emerges from a historical moment when there was a surrealist movement in art, and the problem with the surrealist movement was that there was no visual cohesion: surrealist art works don’t look alike. When you think of expressionism, or impressionism, or cubism, while there is variation within a set of tactics fro making a visual image, there’s also common ground. Surrealism doesn’t do that.

Surrealism does something else, and it’s always been hard to say exactly what that is, and that’s why surrealism is interesting, and still misunderstood. I know what I think it is, which is probably not what someone else might, but for the purposes of this now very elliptical discussion of Liam Ros Baker’s art, I believe surrealism to be imagery that emerges from unconscious or half-conscious states or ideas, or which look somewhat like the worlds we encounter in dream or hallucination. The best examples of this are, to my mind, found in photography, particularly the works produced by Man Ray, Lee Miller and Dora Ma, and you can also find contemporary surrealist work being produced locally by Pat Brassington. And now, by Liam Ross Baker.

The works in this show, and in the Young Bloods exhibition at Despard Gallery earlier in 2023, are uniformly uncanny; they have the slight awkwardness of an unreal tinge, they are familiar, yet not so.

What’s crucial though is this isn’t just happening in the work for the hell of it, just as it wasn’t with the surrealism of a century ago. That movement was profoundly political – it was associated with communism and anarchism; there’s even evidence of surrealism being adopted as a technique by anti-colonial movement in Martinique and elsewhere in the 1930s. There’s a lot more to this, of course, but I want to suggest that surrealism’s destabilising, unnerving tactics, are at least in part a critique of dominant cultures, and when Liam Ross Baker is portraying the domestic space of Australian life as somewhere that is actually a bit weird and a bit unsetteling, that he’s suggesting that there are issues with Australia such as it is right now, and that cracks are showing. It certainly helps that he’s an excellent painter, of course: his subtle but pervasive critique is well carried off by the artist’s skill.

It's pretty engrossing material for an artist labelled as emerging, but that suggests Baker is someone worth following, because it seems he’s very productive and his investigation is gathering steam.

Liam on insta: @liam___ross