Queer joy | November 2023

Hello and here’s the difficult sixth issue, and let’s just note they’re all a bit difficult, but y’know, I love my job. Writing about art is a real privilege, as is seeing all the art I get to see, even the stuff I don’t like – someone did do all that work. I think this is something that’s become quite important to me, over time, is that on some level just about every artist I’ve met is some version of hard working, and that needs acknowledging. Subjectivity is quite a thing.

Anyway, there’s change afoot here in Make and Do land. From here on in, we are not going to attempt to create a listing of every art show that’s on; that turns out to be a terrifying, time-consuming fools errand which delays everything and makes me quite insane. So expect soon enough a ‘this is what I reckon you should see’ with a bit of comment on why, exactly, and dates and places. Let me filter art for you.

I never claimed this was anything other than a work in progress, so thanks for understanding.

I’ve not had much time for reading but I did just (finally) start dipping into Sand Talk, a very awesome book from Tyson Yunkaporta. Tyson completely blew my mind with his presentation-via-zoom at the symposium for the wonderful exhibition Out Of The Everwhen at the Plimsoll Gallery back in May. Sand Talk challenges all kinds of thinking, and is incredibly accessible and readable for a book of quite complex philosophy. Tyson has just put out a new book, Right Story Wrong Story; hopefully it won’t take me six months to get around to reading that one. If you’re not convinced, Tyson turns up on the highly amusing Conspirituality podcast; give that a go as a taster here. There’s also Tyson’s podcast, The Other Others which is filled with some incredible takes and has a massive archive. It’s been great on bus trips or while doing the dishes. You can find that on wherever you get podcasts.

Alright, art stuff ahoy. See you soon.

Ian Terry: Uninnocent Landscapes

Sidespace Gallery, Salamanca Arts Centre

3 - 13 November 2023

This was an exhibition that wasn’t on long enough, and possibly got missed by some as a result, but thankfully, is also a book. Ian Terry, the artist and author here, is an historian; so his art is very much art made by an historian, so it manages to be a different take on the very well worn genre of landscape photography. I must say that in general, landscape photography or art of any kind is something of a hard task for me to really get on board with: it can be excellent, and it can work well, and the artist can be skilled, and I’ll be able to see all that, but personally, it’ll make me want to vomit. This isn’t because I’ve seen too much of it, although I have, but more because in some work I just see unfettered colonial settler issues and y’know, it’s 2023 and we really need to talk about how we’re doing this. I’m not saying we should stop, and that’s unrealistic anyway, because landscape art is an irrefutable pillar of the local arts scene, but if it’s possible for any kind of artist to approach landscape art through a more critical lens of colonialism, particularly if they are a settler colonialist, then I’d really welcome it.

The thing that really grabbed me about Ian Terry is that he’s really giving that approach a go, and he’s doing it with some directness: he has honed in with some precision on the Big River Mission undertaken in late 1831 by George Augustus Robinson, a complex and problematic historical figure. This history is pretty well known, so I’m not going to recount it here in any depth. Ian Terry decided he would follow Robinson’s path and take photographic images that link up with entries from Robinson’s diary, and that’s what he does – and it’s effective. The book features many direct quotations, sitting with the place Terry visits.

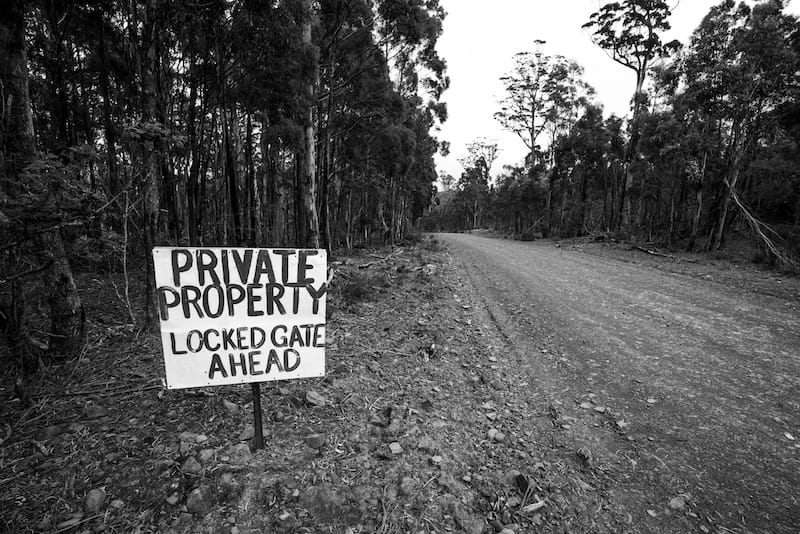

Results are, well, weird, unsettling, uncomfortable. It’s hard to make lutruwita look ugly, but Terry does make it look haunted and spectral. In couple of instances, when visiting a point on the journey, Terry stumbles over subtle things that speak volumes: signs that denote ‘private property’. Locked gates tagged with settler family names. Threatening notices of 24-hour surveillance – on a dirt road out back of the midlands somewhere. A faded ‘shooting in progress’. Earth moving equipment. A Black smudge of fire smoke in the distance. All these things suggest ownership, guarded land, spaces fiercely claimed. These are found quite by chance, but if you want shrewd evidence that colonialism is alive and well in the 21st Century, this is it. He captures mood and brings out the complex, uncomfortable narratives while creating some imagery that manages to not look like landscape photography: Terry has gone to more nondescript, strange places, and photographs a hidden lutruwita – and given that ultimately the work is about truth telling, going to spots outside of the tourist trails serve as an excellent metaphor.

This is where Terry’s project succeeds best: yes, he looks to the past, but he himself undertakes a kind of psycho-georgraphical journey by visiting points on a map that correspond to an infamous historical journey – not re-creating it, but going to the site and looking for the scars. This is what Terry captures: wounded country.

Terry’s project and book has involved palawa people – there’s comment from Greg Lehman, Rebecca Digney, and Naomi Sculthorpe-Green, all who contribute significant observations to the project.

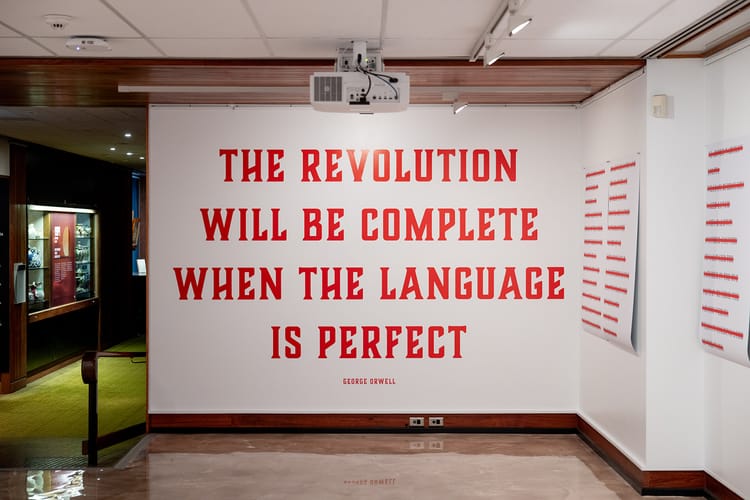

I thought it crucial that Terry has chosen to focus on a settler colonialist like Robinson, and that he allows to us experience the confronting language and attitudes Robinson demonstrates. There’s some shocking stuff dropped in quite casually, and the points Terry makes by doing this hit home.

I don’t know if enjoyed is the right word for Uninnocent Landscapes, but it’s incredibly effective – not in the least because Terry has disguised his work as a Nice Coffee Table Book. It really is no such thing: it’s a settler trying to make a start with a complex conversation, and taking some responsibility for how all settlers have benefited from colonisation, and still do. Terry’s choice to start small and focused is excellent, creating a way in to something much bigger.

Uninnocent Landscapes is a moment where art is well used to create a statement and ask some hard question, and it’s crucial that it’s a settler with long experience in institutions taking the step. Palawa people have done enough. It’s also a strong upending of what landscape photography is and is not, and there’s not one close up of an unfurling fern frond cover in water droplets to be found here. For that alone I would give thanks, but Terry’s done something important here: he’s opened a door.

Uninnocent Landscapes can be purchased at all the obvious indie bookstores in Hobart and in Launceston, and online here.

All proceeds from the book will go to the Giving Land Back fund – find out more about that here.

Notes on Community Exhibitions: Artfully Queer, Artists with Conviction, Minds do Matter, The Poochibald, and Microgravity

I’ve been to a number of community-based exhibitions in recent weeks, and I’ve missed some others, but it strikes me that, when it comes to art writing or criticism, these exhibitions are not all that much talked about or maybe they don’t get seen enough, or something like that, but I love going to shows like this. I also know I’m somewhat doing a naughty thing here by grouping all these ‘kinds’ of show together, but I want to think about the energy that I find when I go to a show like Artfully Queer, and how there’s always a massive surprise to be found at that regular exhibition. Artfully Queer was where I first encountered the Soup Collective, and they’ve become quite an important local entity for me, but there’s more than stumbling over something that’s ‘good’ or ‘proper art’ – which is a weird concept, is it not?

But that’s what a show like this does for me – it asks me what ‘proper art’ is, and why there’s a distinction, and what it means to even have an art world where I can make that distinction, because it’s kind of a horrible one.

It’s hard to illustrate this in theory, but fortunately, I have a good starting example, and that was found at Artists With Conviction. This is a show composed of art by incarcerated people, and it’s always so raw it’s bleeding, and that alone makes it worth seeing. You find art there which comes from a particular mental space, and sometimes there’s something unexpected. There were a couple of things that held my attention, but the real surprise was ‘Here comes the New World, Same, and the Old World’ – a three dimensional diorama of a medieval/Tudor village, with buildings, a windmill, a graveyard and more. It’s amazing because the materials to make art are very limited for inmates of our penal system, and this ridiculously detailed construction was fashioned from toilet paper and is held together with blu tac. As a testament to ingenuity and persistence, it’s astonishing. You really should have seen it. The artist’s statement suggested that it was also a comment on how neo-liberalism was becoming neo-feudalism, and, well, that’s not a bad call at all, and all the more notable when you consider where the message is emanating from: someone completely embedded in the actual mechanics of The System. It reminded me of nothing so much as the Chapman Brothers works, the destroyed Hell and, the still existing, Fucking Hell. There’s nothing obviously creepy about the work, beyond the graveyard, but there is something unsettling about it – this could be the context it came in, as work by an inmate, subtly bleeding in, or it could be the rough forms and the jagged appearance. This work was enthralling, but my major observation is not so much that there’s always a ‘sophisticated’ work amongst the dross, but that nothing here is actually dross at all, and that all kinds of people are capable of all kinds of observations and expressions, and you don’t need to have gone to art school to make art. Which is hardly news, but I’m not talking about that: I’m talking about the effort we make as an audience to step beyond the routines we might have of looking at art and changing what we’re looking for. I don’t go to the Poochibald, an annual exhibition of images of dogs, found at the Rosny Schoolhouse, to see the same art I see at the TMAG or at a commercial gallery, because what I see when I see the doggy images is unadulterated emotion and affection and love, celebrated in a clear way that anyone can understand, and it’s actually genuinely wonderful.[1]

A differing form of wonder is found at Microgravity, a show from Mosaic which is completely essential viewing – you really do encounter completely differing approaches to art here, often fascinatingly repetitive and formally tough, yet compeletly unbound by convention. The works of David Burr genuinely held me: there’s something really intense about Burr’s felt-tip creations that rely on what seems to be a repetitive, meditative technique that really manages to be evocative, and it’s just one human doing something they find comforting. I’d also like to note there was a tonne of amazing art in Microgravity, and that it was beautifully curated and installed, nothing more so than the intense art of Anita Wood – her beautiful explosions of floating colour demonstrate a knowledge of when enough is exactly enough, and like Burr’s have a strong uniform formality that makes her work breathtaking here, presented in an installation form where how much she’s made becomes apparent. Wood is quite psychedelic and her work is lustrous and gorgeous.

I don’t want to condescend to any of these very different shows, because I always get something great from them, and I always look forward to the possibility that something left field is going to broaden how I understand art – it’s rare but it can happen, and it’s only going to happen at a community style show. You need to see something thrillingly, terrifyingly apocalyptic that points to the return of Christ, or a really neat pencil drawing of Ice Cube that’s actually a really good drawing. You need to see a rough drawing of a beloved dog that has died that will rip your heart asunder, and you need to see exuberant, joyful expressions of queer sexuality and being.

I think shows like this are important to see if you love art and you love thinking about art, and they’ll enhance how you see art and what you think it can do. They’re important because they’re from other worlds, and give you insight, and because when you clump them together, even awkwardly as I’ve done here, you get a better picture of what art can mean to a community than a lot of dry statistics driven arguments. You see all kinds of raw emotion, you see longing and love. Yeah you might see something genuinely incredible, but that’s not the reason to go: I go to get how I look at art broken apart, and to remind myself of the great importance of personal expression, however it may come.

[1] Mind you, The Poochibald nearly destroyed me. I was asked by the fabulous staff at the Rosny Farm (whom I have much time for, given the excellent program Rosny consistently delivers) to judge the Poochibald a few years back, and like an absolute twit I said ‘sure’ – and it’s one of the worst mistakes I’ve ever made because that show is impossible to judge. It’s a nightmare. Everything there is so sincere and sweet and delightful, and – God Help Me – there was a children’s section too, with all these exquisite, honest, guileless children’s drawings of their best friend, and there was not one that was not the most beautiful work of art I’d ever seen at that moment. To make it even more impossible, said staff member was guiding me through the show telling the me dog’s names (OH GOD NO PLEASE) and stories about adored dogs who had died or gone missing and the drawing was a heartfelt tribute of undying love (I AM NOW A PRISONER AT GUANTANAMO BAY) and I just kept melting and getting dewy eyed and it was so utterly impossible, but I did chose in the end and I will never know if I made the right choice and this moment will haunt me until the Last Trumpet Sounds. Okay that’s a bit hyperbolic but it was seriously hard to pick anything as being ‘better’ when you knew the emotional weight and if you are ever asked to do this – just do it. It’s a real privilege, and I wear my scars with pride.

.