Languages, rituals, imperialism | March 2024

Yes, it’s March. It’s almost APRIL. Terrifying.

There’s quite a bit here that I need to mention.

I was looking at the Small Artist Collider at Good Grief (which is really good and you should go see it), when I was struck by the lack of labels, titles and artists statements. My god I was relieved by this: nothing to hang an idea on but the art itself, all of which I found super fun and interesting, all of which pumped my imagination in various odd ways. I was wondering if I was inspired to actually dig more out the show by the sheer lack of containment, and – do you know – I think I was. I wonder why we have all that stuff at all sometimes, but there is a point to it, it’s just incredibly refreshing when you suddenly realise you don’t necessarily need any of it, and the art can just do its work.

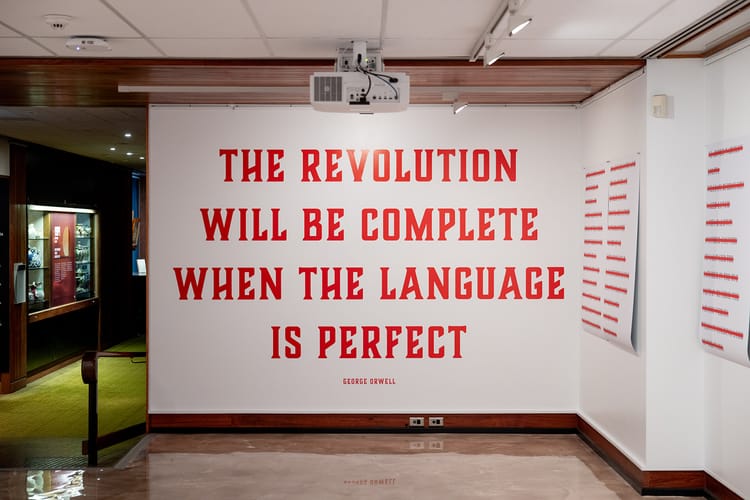

I absolutely love this artwork. Something I’m hugely enjoying in contemporary art is looking to artists from the Global South and from First Nations communities making powerful, critical art that asks big questions and cuts straight to the chase. This work is one of those and it’s tough as nails, funny – you get it instantly – and has so much folded into it. I’m inspired and reminded that art can be where the friction lights the fire. I know it doesn’t happen all that often but it’s good when it does, and it does show you what can be achieved. The artist, Chavis Marmol, is no flash in the pan either – he’s been making great work for a while. A lot more has been written about this work, and it does hits some cultural buzz buttons, but it also skewers the target really precisely.

I want to note the end of Ubuweb. Ubuweb, it appears, will no longer be updated. Apparently, it will remain as a static archive and resource, but if there is one thing I have learned about the internet, and it is that very few things are truly forever on it; so, I wonder how long it might be before the chairs are placed upside down on the tables and the lights are flicked off. If you do not know Ubuweb, you should, so go and have a peruse of it. I consider it to have been incredibly important in my education on art of all forms: it is filled with files and information about the strange and wonderful edges of art, where you might find experiments and sidelines from all manner of people. Ubuweb made it all free and easy to see, and while it operated in a murky territory that was fast and loose with copyright, there’s stuff that will blow you away and you need to go back if you know the site, or go for the first time and dig in.

Here are some totally random things that maybe show why I think Ubuweb is important:

Alice B Toklas reads her recipe for hashish fudge

La Monte Young’s Well Tuned Piano

Cornelius Cardew’s Stockhausen serves Imperialism

Chiptune covers of Kraftwerk songs

Dance by Twyla Tharp to Philip Glass composition

I could sit here all day and suggest simply awesome stuff, but there’s a bigger point here: Ubuweb is free and it has a great, easy to use interface, and it represents a free and open internet that has no commercial constraints. There are so many resources that are locked down and monetised; this is not. Explore it while it’s still there. You will learn as much about art as you could want from this amazing resource, and in some ways, if it goes, there will not a be anything like it again.

A nudge: Clarence City Council’s General Grants Program Round two is now open and, for the first time, they’re offering Cultural and Creative Grants for up to $10,000. If you have a project that could work for the Clarence municipal area (and that could be a great event or exhibition at the Rosny Farm complex), this is still open, and the closing date has been extended.

You can find out more about the process and what you can do here then you can apply here . You have until Monday April 8th.

We’re going to continue to note interesting opportunities for artists here, and if you have anything coming up or closing soon, get in touch.

We started a new aspect of the Make and Do Empire: writing for artists. If you need a bio written, or a hand with a catalogue essay, or you need your resume beaten into shape, or help with copy, or a grant application written... well we can do that (and more). Even the artist statements that I said might not be necessary, above. We have a sliding scale of rates and would love to chat with you about whatever it is you need done. Do get in touch.

And now – some art for March. I hope you enjoy it.

Notes and thoughts on

LUTRUWITA: ALL ROADS LEAD TO HOME

Nunami Sculthorpe-Green, Joshua Santospirito

Moonah Arts Centre

23 – 27 Albert Road, Moonah

16 February – 6 April 2024

Drawings on walls and collage using the detritus of capitalist, colonial culture are ways of making art I really love. They seem quietly defiant: we’re going to write our words on the walls of your institutions. We’re going to make something beautiful from stuff you threw away, from advertising, from the leftover dross of capital in action, capital that leaves its rubbish everywhere then suggest you pick it up; we’re going to make into something that isn’t advertising. We’re not going to sell anything; we’re not going to make objects to sell, not today thanks.

Small acts of subversion are how erosion happens, how slight but significant cracks form, how things get broken apart. Well, that’s what I think. That’s what I hope.

I really liked this show. It’s subtle and its clever.

It’s about... What is it about?

I thought I knew but sometimes it’s good to take a step back, and back again, and look a second or third time[1]. This work has subtleties that are not apparent, but become so over a longer moment.

But I’m getting ahead.

Translation is a weird thing. We get taught it incorrectly. I recognise now that I was taught the concept of translation in a way that was... Well, culturally imperialistic. This word in this ‘foreign language’ means this in English. This implies a whole lot of things, and one of them is that English is ‘first’ and other languages come to it to be ‘understood’ or even ‘correct’.

I’m sure you’re getting this and you probably even knew it, but let’s just follow this line for a moment. I deal with language and words and I make art out it, and I’m interested in the edges of it where it fails and frays and falls down and fails us. I think one of the reasons art exists is that it is a different way to communicate, and I don’t agree with the notion that art exists to enhance status and attract mates[2]. I think it can do that, but I also think it can have nothing to do with that, and this is based around nothing more than the observation that humans communicate, and communicate compulsively.

Language is interesting. It shapes culture but it’s also shaped by culture and it does what we need it to do. There are lots of reason why emojis took off, but it was because there was something necessary or needed about them[3].

Language is complex, and not all languages are related and the idea of direct translation – that this means exactly that – is not possible. The concept of food and when we eat and what we eat changes with a place and what is there, as does everything like tool use – you make swords because you have metal you can dig up that will be effectively made into swords, and if you are in a part of the world where you can’t do that, where there is no appropriate metal, you are not going to have a sword, or a word for sword, and the way you view fighting might be different, and the way you look at conflict might be significantly different. There will not be a word for sword because the concept of a sword is not useful or even relevant. There are lots of things like this, and people over here on a different continent will have solved a problem pertinent to them in a way that is logical for them and where they are.

Language will reflect a culture and a people and be of that culture and that people and it is not a debased version of English, it’s exactly the right language for that place and those people.

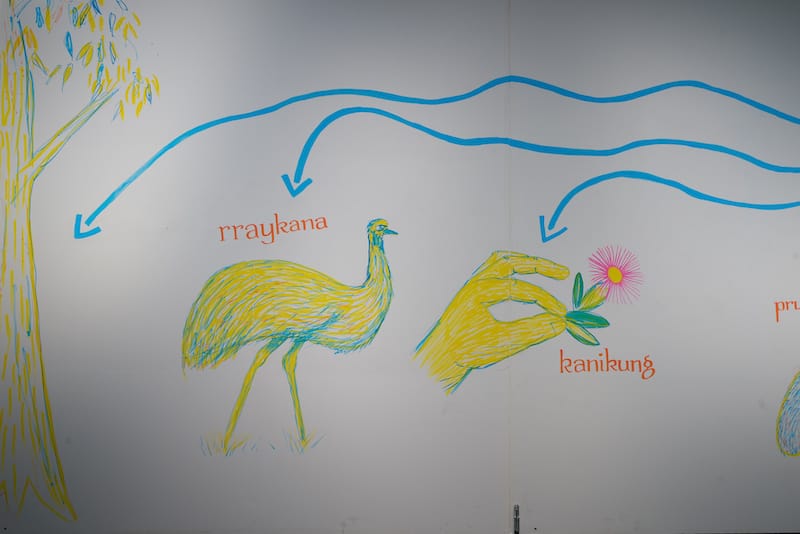

This is what occurred to me when I was thinking about Lutruwita: All roads lead to home, at the Moonah Arts Centre. This is an astonishing exhibition that had a slow burn with me and made me really question a number of things around the idea of language and translation and cultural imperialism. The show is a map of Lutruwita, made collage style out of wat I believe is residual tourism publications, and drawings of plants and animals, and everything is labelled in Palawa Kani and there’s no English translation because this is what these places and animals and plants are called by the people whose country this actually is. Each word is a concept or a creature or a place; it is connected to here, and it’s not a pale echo of something from the Northern Hemisphere.

You know there was moment when what we wrongly call a wombat, which is an approximation of a word effectively stolen from the Dharug people who lived in what is now called Sydney, were called badgers, so there are place names like Badger Creek and Badger Corner, but it’s really prupilathina. This is important because a prupilathina is a different animal and not even remotely a badger.

But Imperialism overlays and ignores and pretends.

This exhibition itself arrives from extensive work by the Palawa community and language program. It revives and revitalises culture and it’s quite amazing: there is so much work and research here. Palawa Kani is a whole language, used within community. In a spirit of astonishing generosity, some words are essentially offered to the broader population so they might be used. I found this quite humbling, and interesting, and it made me think of how crucial it is to identity and culture for language to exist. It also made me realise this exhibition wasn’t really aimed at me[4], that it’s actually for Palawa people in Lutruwita, but that it’s alright for me to use these words as well.

The show ends on Saturday the 6th of April, so there’s time for a look if you’ve not been. I enjoyed it in the first instance, but it’s stayed with me and there’s something truly powerful about the statement made by just using Palawa Kani words. Something obscuring is being peeled off, and something else, something that is of the place of Lutruwita, is revealed. It’s quite wonderful.

Notes on A DANCE RETOLD

Leyla Stevens

Contemporary Art Tasmania

16 February – 23 March 2024

Sometimes, I hit a show I like so much that it’s hard to really get to grips with. This was almost impossible. I don’t know if you know this (some of you will), but I make art as well, so this will come as something of a confession.

I used to make this visceral, dark, performance art. It could feature self-harm and performative mental illness, and it was hard to do and it hurt. I loved it, but I stopped. I keep thinking it’s not over, and it probably isn’t, but it stopped. Things come and go, and I still have axes to grind and demons to slay with my scratching and picking at art, but for now, I write and I watch and I wonder.

A Dance Retold took me back to everything I loved about making ritualised, dark performance art. I didn’t see myself in this exhibition, but I have had a small glimpse of the energy this dual presentation of films about Balinese women and performance just exudes. I know, as well, the yowling wonder of extreme metal, which this work also visits.

I love that stuff – and I love it uncritically. When I am fortunate enough to encounter the workings of ritual from another culture, I am humbled by the sheer vastness of a whole cultural tradition, and how it makes me I recall how small I am, and how I fumbled in the dark, trying to say things about my body and myself and pain and transformation. I must point out that I don’t want to copy the work shown here – that works belongs to the ancient supernatural worlds of the Balinese people, and I am fortunate to even be allowed to see it.

Leyla Stevens presents it incredibly well; finding issues and sharing them: cultural memory, the magical power of women working with their culture, issues of identity, issues of gender, all are found here: issues of imperialism and appropriation too. I was most powerfully reminded of how ritual is organic; how you cannot fake it, and how when it is convincing its beauty is a dark red light that brings the noise, that lures you into a space of trance, where you meet people who have become, really become, supernatural entities for the moments of the ritual. I know that sounds weird, but I relate to this and to me, the transformation is utterly real[5].

Watching film of a rehearsal, watching women find their way to being something powerful and potent was hypnotic. Groh Goh, the longer of two films, really knocked me over with its visions of dances and demons, of women sharing stories and interacting, and then transforming until they seem to become the witch-demon Rangda, a terrifying, charismatic force, made the hairs on my arms dance with electricity. I was utterly transfixed. I was lucky to see it alone, so I could simply dive into it (and I am so sorry to the patient gallery attendant who put up with my gushing).

I don’t know if everyone would click with this the way I did, or think I did, but I do know this was totally exceptional contemporary art that reveals something raw and gorgeous that our culture doesn’t have, and is all the poorer for it. I could also see how the second film of the two discussed the removal of culture – it showed a collection of beautiful Balinese painted artworks held in the sterility of a museum – and the way in which a ritual dance seeks to reclaim that which was removed[6], that which was stolen, that which sits in climate-controlled storage, transformed to a holding rather than a living document.

But really, A Dance Retold just hit me in my gut. It slipped inside my head and I was thrilled, and when I think of it now, I still am. Some art comes first as a feeling, and I felt this, felt its weird beauty. The ideas came later, and to be frank, the ideas still come – the effect of this work is long, and I may continue to piece it together for a while yet. What I want to capture right now is the important moment where you find an artwork that hits you in your gut, in your body, that thrills you out of nowhere.

[1] This is a real side note, but there’s a thing that sort of irks me about how rapidly exhibitions turn over. I like to try and see everything, and I don’t, and I can’t. I like to go back more than once. I like to sit and look at one work and if it’s one I can find a connection with, I can watch it change in front of me. I have a grand idea that art – or rather how I see art – can change over time, and that my mood will affect how I see art, and the weather, and everything. But so rarely do I see a show more than once, and not really for that long, not really.

[2] My oath, could I go on about this one. It’s just such a narrow view

[3] I have been itching to write a review entirely in emojis and memes and I have never told anyone but here we are, and here it all is. I probably won’t be able to make it work, of course.

[4] Knowing I’m not the target audience is important at times for understanding what a story is about – the audience is as crucial as the art, and not everything has to cater to me to be relevant.

[5] I have to note that it’s real because art is real and some art is transformative. That’s what it does. Some art changes you, perhaps only slightly, but such things can happen. This can simply be accessing new knowledge or perspective

[6] The issue of the removal of art to be held in a museum is huge one; we are in an era where this is changing and being examined – and so it should. The conversation is incredibly important, because it’s about dismantling the effects of colonialism and trying to make reparations – but it goes further, questioning how museums and institutions actually operate.