Two things that feature rocks

Hello.

Here’s two things that feature rocks. That was a coincidence, but when I noticed it, I had to sit these together in my head, because I like that kind of synchronous magic.

At the moment I’m thinking a lot about what art can do, and here, in these exhibitions, I found art that could do a lot, and I was pretty gratified by it. More than anything these shows made me think about art’s potential to be a tool of activism, provocation, and social comment. I was also reminded that art does not have to provide all the answers – indeed, I think might even be better when it doesn’t.

AS A ROCK

Lucy Hawthorne, Priscilla Beck, Tim Panaretos & Gabbee Stolp, Lucy Parakhina, Anna Eden, Edith Perrenot, Madeline Parsons

Curated by Rebecca Holmes

Notes and thoughts on an exhibition.

This exhibition is something I hope everyone in ‘the local arts scene in Lutruwita’ went along to because it was a near-master class in how to put an exhibition together, and I want to really note what an excellent job Rebecca Holmes did here.

The work was diverse, the overarching theme was clear and also open to interpretation, and there was just enough work here for it to not look too light on, or too dense. Some works were even at odds with each other – which was fascinating. This created a kind of useful tension in the show that did much to provoke dialogue and consideration of issues I sort of never had, and question a few of my own behaviours. To be asked to think about an issue you’d never really even considered before is a good thing, and then extrapolating out from it is even more rewarding.

The art itself was all excellent; I was particularly excited (really!) to see some gorgeous collected prints of Lucy Hawthorne’s Performing the Abels. Lucy’s someone who heads off into the wild on a regular basis, and has made a series of images of herself clad in a gold hooded cape affair. Lucy is in them; she gets whomever she is with to position her as the performer, and choose the composition. The series has been ongoing for a while; I was already well familiar with it from social media, where Lucy has traditionally shared the results. Seeing them as quality prints, in series on a gallery wall was surprising; larger and collected, the images informed each other, and I had a better idea of the commitment that makes these works. Lucy herself has her back to us, her form is obscured, and her humanity somewhat blurred – we only know it’s the artist because we’ve been told this. She’s sitting down or hunched, yet glaringly obvious because of the gaudy apparel.

I like the way this work becomes a long personal ritual, or even a strange take on making a pilgrimage. I like the way Lucy has to carry a special garment, and has to have someone else to make the record, and how she gives control away in the crucial moment. It’s decidedly non-macho, which is useful, because sometimes I can associate the endurance and effort with a kind of conquering of spaces and places; I don’t see that here. Lucy is more celebratory, even joyful; when she gets to the top of a mountain, she puts on her garment and momentarily transforms into – well, something that’s part of celebrating the beauty of a place, and the idea of ritual and effort. It’s a wonderful work, and the manner in which it is spaced out over time, and gently shared as an experience, makes for some unique art that is very much derived from the artist’s character and world view.

Priscilla Beck’s work caught me off guard, and shifted the exhibition for me. The main idea here is Priscilla was taught as a child not to remove rocks from where they’re found. This is one of those tiny things that sends a seismic shift through so much of how I think – because I pick up rocks. The question of why I do that is fascinating – am I trying to possess something? Is this the behaviour of the coloniser?

One of the things I consider as I examine what it is to de-colonise my own learned behaviours is how much of it is made of tiny practices I don’t even notice, and how much I need to actually think about why it is that I do anything, where I learnt something, and how I un-learn it. I don’t recognise a lot of stuff that I do – it’s so ingrained. This is interesting and confronting to a high degree, but if we are to make genuine changes in this sphere – and I’m someone who considers this a good idea to put into practice – what needs to happen is genuine self-reflection and unpicking of the smallest conditioned behaviours. Priscilla here provides a great place to start, largely by pointing to what is simply a different understanding of land and place and space and how we interact with it. I was actually quietly floored by this work – it got right in under my skin.

It gets more interesting when you consider Edith Perrenot’s work – which is a kind of altar that offers you a place to put those random rocks you’ve gathered. I kind of loved the community offering nature of this work – even though it sits to some extent in a frictional space to Priscilla’s thoughtful offering. What’s interesting is that Edith, like Priscilla, is aware of the practice of rock removal, and is attempting to do something about it – there’s a form of respect for the misplaced implied, and this space to place is something that takes place after the rock removal has occurred. There is no actual solution to this friction between works though, although it is fascinating that we have two differing artists approaching and commenting how rocks get moved around, and question what it is that happens to them. Edith has an aesthetic that’s really charming, and it’s in full force here, and making somewhere for rocks to be has some merit, and she underlines that the rocks are not where they are supposed to be – and the idea that rocks are supposed to be anywhere is potent.

Gabbee Stolp and Tim Panaretos have used found rocks from their front yard, and cloaked them prints of rocks – or a rocky place – from their respective childhoods. There’s a lot here about being in a place, imaging a place, and how we think about land and where we are. It’s not complex work but it’s got depth and does what I need art to do the most: ask me something. This asks me about how I understand an idea of home, which is a question that is simple, and unending. My childhood home, my parental abode, is not a home for me now: so like anyone, I’ve had to make something else. Here is the new wrapped in the memory of the old: it’s an echo that has a new weight, and I wonder if that will be enough for anyone to shelter in?

Madeline Parsons makes truly gorgeous paper sculptures of what I see as crystalline forms. They are idealised images of rocks and I find them oddly psychedelic, slightly strange and certainly evocative. Madeline is balancing something: the forms are seemingly randomised polyhedrons, yet there’s an obvious control and order underneath their creation (which is by patient folding) and placement. I find myself thinking of them as constellations (rocks in the sky?) which I read patterns into. There may or may not be an actual order here, but I’m a human: I look for order, I think there’s a cypher or a code to be deciphered when there may well not be – and that’s fine for me to do, although the wonder in these paper sculptures is in the making and the time that goes into them. They’re such patient creations.

Anna Eden’s work is complex: she had made rocks by collecting the detritus of her existence – and performing a process that mimics the way rocks are formed. Deeply strange because it truncates time and geological process, but it’s also gesturing to that time and process, to the enormity of geological shifts; the dichotomy making Anna’s output really engrossing. I was really taken by this work; I hate picking favourites in an exhibition, but I must admit that the aesthetic Anna really appeals. There’s an abject component to this work – you realise that’s literally the sheddings of a body – but it also suggests a cycle of decay, renewal and the process of exchange under which all bodies inevitably go – we will decay and become something else. Anna lays this bare and dares to even celebrate the process – which is a bit like composting to my mind, or any kind of naturally occurring process. This creative tactic was presented in a really thoughtful manner – a kind of altar was created, the objects were balanced, and vaguely reminiscent of art of Rothko. A strange supplication to a transformed body was suggested, or the inevitability of cycles, or something beyond regular experience, of some kind. It was weird, and abject, and complex, and suggested a strange biological alchemy, and I can’t think of much quite like this art. This possibly displays my limitations, but I feel Anna Eden really nailed something gloriously weird with this exercise in transformation that perhaps hinted at a desire to shift humanity to something else.

Lucy Parakhina’s short video is about mining. Mining... it’s hard to know where to start and where to stop. I feel I could make a list of everything mining does and means, and this list would go for a week, but let’s not do that; its more interesting to note the existence of an artwork about extractive processes and capital. This was the perfect exhibition for this kind of work: it fits the theme and sits in concert with other works here. It’s where I found a possible overall thesis for the exhibition as well – and let’s note, this is me overlaying this meaning – just as I look at Madeline Parson’s art and look for a pattern to examine, so to do I look at the whole selection here and see what I can read. I should note I do this all the time with art and art exhibitions, and it’s how my mind works, how I think, and why I write about art: I build worlds and interpretations. I don’t think this was a secret puzzle for me to unpick here, either; I just think art is terribly interesting and it makes me think about the world. This work does exactly that: I think about the scarred surface of the earth and the damage mining does, and how that is linked to capital, and how there is not enough regulation that takes responsibility for the damage that extractive capital causes. Think of that in relation to Priscilla and Edith’s works here, in concert with Lucy and Madeline who make these slow beautiful things, with Anna and Tim and Gabbee who have made homages to rocks, to fragments, to the earth itself as one big connected thing, and in making their modest pieces gesture to huge swathes of time and the slow motions of geology.

What I do see though is that the exhibition wasn’t tied to a thesis, or a message, it had contradictions, and it had rich ideas that allowed me to form something of my own, and that was generous and smart. As A Rock was cohesive enough to suggest potentials for interpretation, but also had enough room to encourage me to fill in gaps, and reflect on what a really good exhibition can do. I don’t know that there was an intention of activism from Rebecca Holmes, but inviting comment on something like rocks created a possibility – and this was taken up in a variety of ways that at least encouraged me to reflect. I’ll be thinking twice about pocketing a beautiful stone when I see one now, and thinking about the power of small, cumulative moments of respect, and where change really comes from.

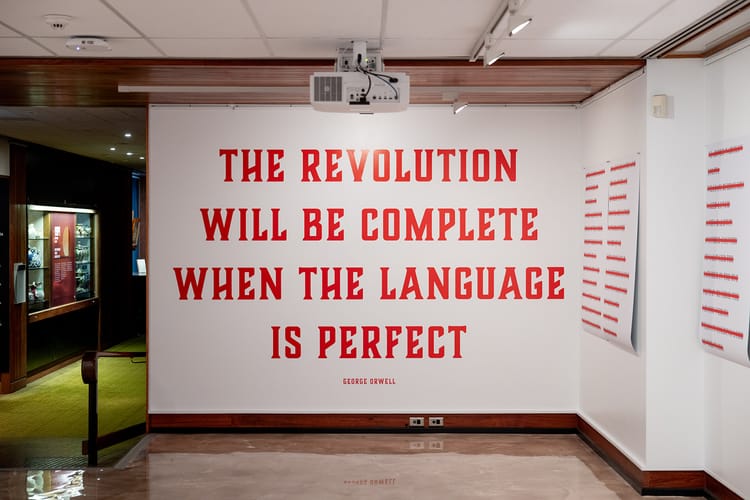

THE LANGUAGE TO ARTICULATE OUR UNFREEDOM[1]:

THOUGHTS AND REACTIONS TO LOST BEDROOMS

Jonny Scholes

Rosny Schoolhouse until 22nd September

Okay, so we’re seeing a lot of art that has an activist bent right now. This is good, and this is timely, and I’m very happy to see it. I don’t require all my art to be like this, but it’s interesting how we can view it – I can, for at least one take, view it as taking a form of responsibility, and that it’s fine to work from where you are, and work within your context and constraints. If you’re a large commercial operation that has a responsibility to a whole lot of artists, it’s reasonable for you to be prudent – but it also suggests that it’s reasonable to find a way to work with that – you can make a gentle, subtle point, and make it well, and you can reach people others will not.

You can also take the symbolic gesture of throwing a rock at window, and make something out of that. Throwing rocks is not subtle, and everyone has done it, and it’s how David took out Goliath, and it is about aim and precision and choices, subtle or no.

I don’t think Jonny Scholes is advocating throwing rocks, but he has taken that activity, and made something really funny and sharp. It’s pretty simple, although not in execution (I have no idea how Mr Scholes does this stuff), but Lost Bedrooms is filled with potent fragments that place it in a complex web of possible readings.

Alright, what is it?

I am going to release the feline from the carryall and just tell you: It’s a robot that holding rocks on a string. Each rock is joyously positioned above a print, on glass, of a bedroom. Each bedroom is real, and each somewhere in Greater Hobart (I believe). If a dwelling that is for rent receives planning approval to become a short term rental (that’s an AriBnb folks), and this information is published on the relevant web site, the robot will receive the information and drop the rock, smashing the glass and symbolically destroying the bedroom.

Shards of glass will tinkle to the wooden floor of the Rosny Schoolhouse[2].

It's not subtle at all, and it should not be.

You can see what this is about: it’s about housing and availability – but it’s also about how despite the very obvious issues and much public outcry, the process of accommodation that is long term changing to short term, and thus becoming out of reach for people in already cramped and overpriced market.

This is happening right now: Jonny has made a model of it happening, and he’s made as a quite brutal analogy that’s also comedic – there’s a kind of glorious slapstick tension and even possible violence here; I can almost hear the artist saying, ‘Oops’ and grinning if a rock falls and the glass shatters.

There’s a Schrodinger’s Cat feel here – what is the status of the room, of the glass, of the house? It’s in limbo, and we may not actually ever know – which is also interesting, because it’s entirely possible that no approvals will occur while the work is installed, and nothing will actually happen.

This means the work might ‘fail[3]’ – but that would be a good outcome.

Now that’s interesting: the best possible outcome is if these rental properties do not become AirBnbs and Jonny’s work does nothing, if there are no breakages. Have a good look at that dichotomy: this artwork’s best outcome is for nothing to happen – and for us to see that nothing happened. Because the existence of this work is unlikely to stop anything, however, does the work also fail if a rock does fall?

No.

It’s not actually about that. It’s about seeing and visualising an arcane, backroom, bureaucratic process that we are not privy to, and making it visible. This is quite brilliant, because one of the problems we face with a lot of contemporary activisms, is that we are talking about things that are kind of hard to see, and certainly difficult to work with. We know there are homeless people, and we know bedrooms are disappearing, but often it’s just numbers that tell the story, and that can be hard to grasp – which is perhaps an answer to why people are not doing more about many kinds of pressing crisis.

This is where art is actually potentially very bloody useful, because art can, if done correctly (and that’s harder than it looks folks) can make something more real to an audience – and a shattering image of the safe haven of a bedroom is pretty real. We get this, but the work makes it real, and makes the implied violence of merciless capital brutally apparent in a way that simply quoting figures can’t.

That’s why this work is so good: you get it, you can see it, it’s an analogy but it’s right there in front of you; the tension is palpable, the problem is real. It’s not like you didn’t know, but here it is. Have a good look at it. Look at the images of beds. That’s important – Jonny shows us a bedroom, a bed. A place where we can sleep, rest, feel safe.

I think about what it is like to not have a bed. To not even have the potential for a bed. To not be able to sleep, rest, feel safe. I think about this because the art showed me a bed, a bedroom, a shelter.

This work brings that out. It’s not an unavailable rental now. It’s unavailable safety. It’s rest that someone will not get. Broken sleep, shown as broken glass, which hurts.

The work and its title ask you to examine the language used to talk about the issues related to accommodation. It asks us why the language of the market and the ideology of the market has infected so much about the way we communicate. It’s 'Lost Bedrooms', not 'Unavailable Rentals'. This is one of those moments when I am forced to reflect on my language, and wonder about how much I use market-speak, because when I start thinking about that, I start thinking about why we have issues talking about any of the overwhelming problems that our community faces, and how much we get wedged into a position of stasis.

This something art can do. This something art can do well, because by its nature it outstrips and critiques jargon. You see the problem: it is laid out for you. Because it’s simple and direct, it sidesteps the phrase “it’s complicated”. Because it uses rocks and glass, and because this already comes with its own context, it literally breaks the ideology that limits and directs how we discuss the issues that confront us.

The choice to focus on one very immediate, very local issue, is part of why Lost Bedrooms is so strong a work. I was thinking about the work as I did the dishes and the realisation that the process of bedrooms being lost had not halted despite so much outcry made me feel sick. I thought a homeless human in a park, right next to an empty academic building and I felt rage.

Homeless in a park in this weather, in these high winds – that relate to climate breakdown.

And that’s how things could happen, how there might be something better: we need to see and feel some anger, and more anger than we already did, because clearly, it’s still happening, and it’s made opaque by a cloud of jargon and statistics, that limit our ability to critique. That’s why this works: nothing is simpler than a rock smashing glass.

I do not advocate throwing rocks, but making a sharp and realistic point you can (metaphorically) cut yourself on has merit.

Go and see this art. It’s very good. Maybe you’ll see that something has broken. Maybe you won’t.

Or maybe you might realise that something much, much larger is broken.

[1] Slavoj Zizek, Welcome to the Desert of the real. Yes, he stole that from The Matrix. The Matrix stole it from Jean Baudrillard, who used the phrase in a book about the relationship between reality and symbols, and how we construct existence – which is quietly floating in the background of this artwork I’m writing about today, because it’s a beautiful confluence of symbol and reality. Or it’s just art. I dunno. You tell me.

[2] Jonny Scholes is working in a manner we don’t see all that much locally – he’s using code, and robots, but the big aspect that I’m fascinated by is his use of readily available data. In one way, what Jonny is doing visualising this data; which we are all familiar with, but it’s cool to see data presented in sculptural form. I’m starting to see a palette from Jonny with this work too: one of the things I really like here is that there’s a number of aesthetic decisions that are important to how this work is presented, but it’s also tied to a number of things that have to happen for the work to, well, work.

While we’re here, using photographs from real estate websites fascinates me NO END, because something that is possible unintentional (which could be selling Jonny a bit short, actually), is how much I could see a kind of very odd aesthetic that exists in pictures used to sell housing and property. Why are there beds? Why do the beds all sort of look the same? Who takes these pictures? They’re framed and cropped and clearly lit in a certain way. I find them deeply weird – one of those accidental un-aesthetics of the market you seen thrown up. They remind me of those accidental abstract works you see when a council worker paints over some graff with a colour that doesn’t blend into the wall. Of course this is all eye of the beholder stuff, but when I am asked to look at a collection of disparate pictures that have originated on real estate websites, and I see they all have a discernible aesthetic, I can’t let it go past. It DOES become analogous with my notions around marketspeak, around corporate language – this is what it looks like, but it’s so totally not real. I mean if you moved into that house, you will need your own bedspread. That fetching lilac will not be there, and that light was clearly a tiny bit retouched. It’s not real; it’s a representation of what we are supposed to think a home means when it is defined by its market value above every other aspect.

[3] I must confess I am incredibly interested in failure as a notion in art – and how tied to a notion of a certain kind of result that actually is. This work is incredibly interesting because it makes the notion of failure opaque, and asks what the purpose is here? You can stretch this out to a broad critique of all art, and other things, that claim to be activist works, and there’s element of Lost Bedrooms being very useful for that kind of a discussion – and to be clear, I think the work is successful for a number of reasons, even if it ‘fails’ and doesn’t actually break any glass panes.