The art I ate in June 2024

Alright art fans – here’s no less than four bits about shows that I saw of interest.

They were not the only things I saw but I kind of ran out of time here, and maybe six bits would have been a bit too much - or maybe four is too much, or not enough, and it’s freezing and I’m wearing really thick socks as a matter of sheer survival.

I don’t want to complain too much though, because this sort of winter weather, when it is not utterly drenching rain, is incredible. Those totally clear days of full blue, cloudless stillness that sound exactly gently stroking the fine edge of crystal glass: high, clear, sweet and crisp.

It’s not a bad trade off for being so cold I have no functioning extremities.

Before the art notes below though, next issue means we’ve been doing this for a whole year (cripes) and there’ll be some ~ STUFF ~. So tune in, and the goodies and ranty opinions will be thrown to you electronically.

I would once again like to note that Make And Do exists due to the support of Arts Tasmania and to a an incredible group of paid subscribers who get extra content, and we really love you all a huge amount.

Stay as warm as you can but do venture outside as well, there’s some fabulous art out there right now.

SOLSTICE

Tilley Wood

Penny Contemporary

I just wanted to note this exhibition. I really enjoyed it – or rather, I found it very moving.

The premise had a modest elegance: Tilley Wood made a series of paintings and sculptural objects incorporating flowers and timbers, and it described her movement in time through a year, from Winter Solstice to Winter Solstice. Tilley has a well-worked painting style that explores gesture and has some common approaches with an expressionist tradition; she works in oils and paints onto wood, making frames from Tasmanian timbers. Her sculptural pieces use dried flowers and reclaimed Tasmanian hardwoods. It’s all quite clean and elemental, and you can really see her hand in all the work – you can imagine her making it all; she’s very present in all the work as an artist, and the work is very much about her filtering her experience over time and seasonal shift into images.

The journey is an emotional one: this is made very clear by one work, Remission, which describes the fragment of time when Tilley’s partner was pronounced to be in remission from a debilitating illness.

I don’t think this is what the entire show is ‘about’ – but there’s a sense of that very personal, and harrowing, story being, if not the spine, then a major organ of this body of work. It’s refreshingly bold to share this, but also to do it as modestly as Tilley does. The passage of time is inevitable, and this marking of one rotation of the earth we all survive on, punctuated and framed by seasonal images and the suggestions of trauma and change, made for an exhibition that proudly revealed genuine human emotion.

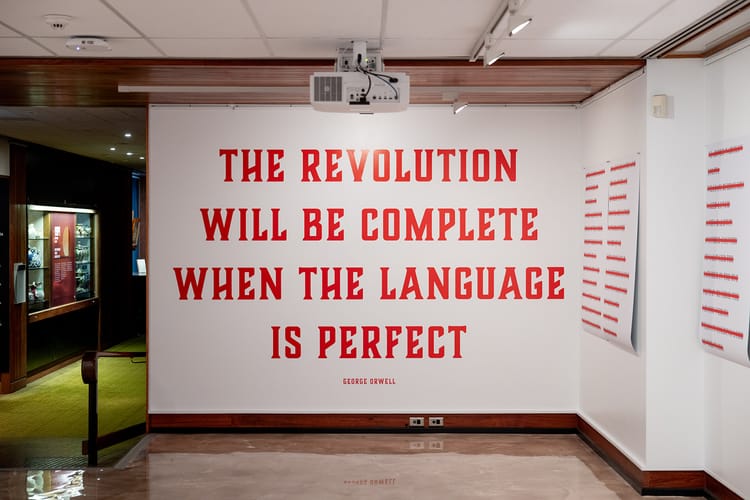

THE BLUEPRINT

Noah Johnson

Plimsoll Gallery

I write and use words in my art and how I create things. I’m a compulsive communicator, and I see myself as a human who tells stories before I see anything myself as any other thing.

I love stories and I am forever amazed by how stories are told and the ways and means that diverse people use to share the stories of their lives. There are so many ways, and I keep seeing different methods used and it’s something I continue to be amazed and even thrilled by.

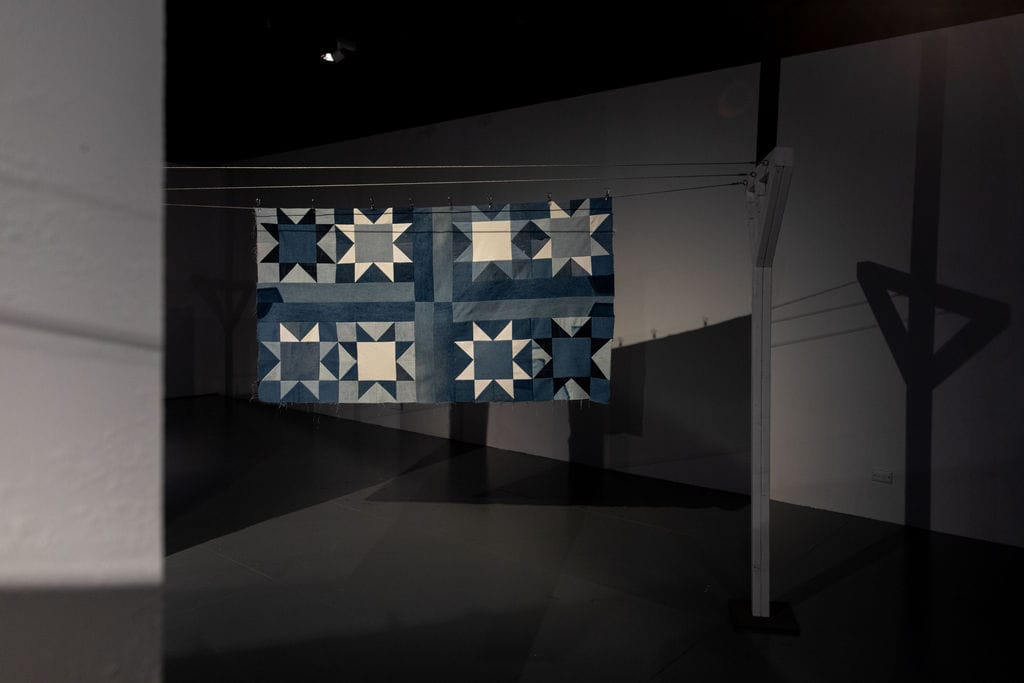

Telling stories and communicating with textiles and fabrics is something that I have developed a fascination for. I have, slowly and gradually, found out small fragments of information about the widespread practices involved with quilting, and how making quilts is a way that families and some cultural groups create narratives about themselves, how they pass information across generations, and how the very physical act of making such a thing is powerful – it is resistance, identity, sharing and creation all in one.

Noah Johnson, better known as De Recycler, is down with all that history and how it works – you can see it folded into the amazing stitched patterns that I saw at The Plimsoll Gallery when I checked out his show. It was tremendous fun to dig into, and was one of those shows that actively unfurled before me like an opening bud stretching with the sun: one idea led to another, in a chain of narration and invoked imagery. I found the show one that was very alive and vibrant and very much of this moment in culture and politics – which one might not consider really when one is going to a show that’s about making clothes – but more fool me, because uses culture and history as material just as much as he uses cloth and thread.

I found myself almost immediately prompted to furtive research in the gallery – I grabbed my phone and began shuffling along the electronic ether, looking for the history of jeans, blue jeans, and thinking about what jeans are, what they stand for[1].

I associate jeans with a bunch of things – rock and roll, the working class, Bruce Springsteen’s arse and all the many other things you could list. Noah added to this for me, creating a new context that kind of rolled my over – he points out how jeans are made, who makes them (people working in sweatshops and not getting remotely properly paid), what they are made from (cotton, which has unavoidable connections to the global slave networks, and thus colonialism, exploitation, horrendous oppressive violence and every other thing implied there).

Noah takes the jeans and cut them up, and this is practical and how best to re use the material, because Noah makes clothes by re-using, but it’s also a symbolic act: the jeans do not look like jeans anymore; the cotton is being re-used, its story changed, re-written. It is perhaps a powerful act of transformation that Noah undertakes, something I can understand as a ritual, as urban magic, as the use of long creative traditions. It is also a statement that critiques the issue of fast fashion[2] , and that re-using and re-purposing material is totally necessary in a resource hungry world.

Noah’s work addresses historical issues and very immediate, contemporary problems, and I haven’t even mentioned what he makes: Noah cuts the jeans until they are not jeans, but still have the history of jeans: He does not disguise this; he actively shows it by making a feature of the material that was hidden in the pocket of the jeans and thus has not faded. The history is not hidden, it’s made into a feature: he wants you to know, to see, to understand, to think.

The jeans become large patterned sheets that look like quilt patterns, and have the language of quilts. They're like a collaged note that sings a new song, words taken from conservative magazines and outdated encyclopedias and made into a manifesto about recycling and decolonising:

The quilt pattern is that, is a manifesto, is a new song made from an old one.

It’s Public Enemy sampling Slayer.[3]

This will be transformed.

You will know its origin, as that must be part of the story, but we will change it: we have the tools and the will.

Am I reading too much into this work? Probably not; it’s all there to be read; it’s a story made of many parts, all of which are derived from Noah’s own background and narrative as a Black artist. That knowledge of history is so strong, and seeing it being used to inform the creation of clothing and textiles gives those textiles resonant power.

There was just so much here I liked, that I could understand as a way of creating work – when it comes in like this from so much cultural background, research and knowledge, everything becomes symbolic and has potential to be read and understood as something more. Why is there are recording of a sewing machine at work? It could just be a neat field recording with an interesting sound, a small sonic document, but it implies a lot more – the existence of sweat shops, where labour occurs and people are deeply exploited. What people? Migrants, women, people of colour – all are hinted at here. Noah is running his own business, but he knows this is not as it was historically, and the people who did it tough, and still do, are here in these sounds and the narratives they imply.

What was really interesting for me here though was the way Noah takes a lot of disparate information and makes the connections visible. The history of the slave trade is linked to the history of cotton, of clothing, of blue jeans, of fast fashion and contemporary labour exploitation, and how this kind of exploitation has not ended, and is part of something as fundamental as the clothes we wear.

Have a think about this, Noah suggests. It might be important.

It's not all critique though – Noah also shares quite openly his working images, his process and his outcomes. It’s like a suggestion of how you do this, or how someone might: the process is not made arcane and shut behind closed doors, it is made visible – there’s video of Noah working, sewing. We know he makes this work, and there’s a suggestion that others could take on his approach – there’s something quite empowering here.

The Blueprint is ideas into action, with direct outcomes, that describes a clothing design practice that is composed of knowledge as much it is physical material. As a part of the overall Motion Sensor experiment with work in progress it’s a total winner – this is the current art I did not know how much I needed to see, which is fabulous, and also reminds me: I have to get out more, look harder and ask more questions, because this work is just too good to miss out on.

PATIENCE

Sarah White

Sidespace Gallery, Salamanca Arts Centre

There are some exhibitions that really do sneak in and out like a thief in the night, barely on for a week.

This was one of them, and it was a bit of a shame because it deserved the opportunity to be seen by more, as Patience was an elegant, precise and genuinely alluring body of work. I have developed something of a fascination with the world of botanical art – it’s a place where art and science truly overlap, where patience and skill are paramount for good reason, and there’s something about the microfocus in to the depiction of a single plant form that I find meditative and singular. There is older botanical art that arrives as the record of the era of Imperialism, and it’s something that deeply intruiges me – part of the colonial project was the cataloguing and labelling in European languages of flora and fauna, but that project also created important records of what places were like in pre-colonial times. They can also be aesthetically mesmerising – the skill required to accurately draw plant forms in an era before cameras is something I will probably never not be impressed by, no matter how problematic the provenance of the image may prove to be.

Botanical art still exists, and it’s important for scientific record. Photography has not replaced it; it has a useful function. To me it’s possible for it to inform other art, or for the techniques of botanical work to be applied to other forms of art. Sarah White has a background in science, but moved into making art in 2015. Her images in Patience are combinations of painting and paper carving; when I first saw them, I thought she’d actually collected leaves and incorporated them into the work, but closer examination showed me that no, these were paintings. The delicacy of the palette used expertly depicts eucalyptus leaves in subtle stages of decay, that are used to create symbolic images that sit upon many layers of carved paper, that suggest a near-infinite recession – while still, the images are mobile and suggest a process of decay and time. There’s something about the works that imply a kind of sensual evocation – the works are a construction, a very precise one that is meant to imply something significant.

Patience is a good title – the cutting and creative process here feels so very controlled and precise, and there’s use of letterpress – some works have single words, some are just carved paper, delicately cut into layered leaf shape, or in one case, a rippling sphere that suggests profound contemplation.

Patience was a kind of art that I saw as very still, precise and contemplative, suggesting decay and slow transformation, and the moments in life where you still and quiet, breathing and wondering.

I thought of bodies and books, unsent letters, the times we wander and do not say much, or say nothing even, and that’s enough. I thought of decay and how it is implied in everything, and how that its subtle tones can be so very sublime.

INVISIBLE POWER

Annie Geard, Bliss Sandhu, Keryn Fountain, Nancy Mauro-Flude, Natasha Bradley

Curated by Natasha Bradley-Cross

Social, Salamanca Arts Centre

Group shows can be really hard to write about. Sometimes they just jump out at you with a clear thesis as to why all these works of art are hanging out together, and sometimes they don’t.

I have a kind of conceit with these things: can I glean, without looking at an artists statement, why all these works are hanging out with each other? Why are they all in the same room? What’s the reason behind this?

There doesn’t need to be one, of course – the recent Good Grief show, Artist Super Collider, didn’t have a really obvious premise, but the works did all speak to each other, and it was an excellent show, with the whole being greater than the sum of its parts. It helped a LOT that the works were already interesting, and something that was important to my understanding of the show was that it was set up as an experiment to begin with – what happens when we get these artists to work together? What will the result be? So it sort of couldn’t fail on that level, because something was inevitably going to happen. So we can say that premise worked.

Invisible Power was different to that. The actual art work was all pretty good, with some work being very engaging. Natasha Bradley’s enigmatic sculptural work that incorporated a video of a group of women interacting in ritualised manner had a certain mystique – there video was set into a structure that had the feel of an altar without being too obvious – there was something slightly occult about the structure and the video that really succeeded. This piece was the absolute centre of the exhibition for me – the gathering of women one viewed were clad in robes, their moves were subtly choreographed, there was narrative but not overt narrative, and what was happening seemed potent. If there was Invisible Power, it was here, in the exchanges between the participants.

This was neatly echoed in Nancy Mauro-Flude’s work, Our Motherboards are Temples, a performance still of a woman displayed various totemic items that suggest travel and the connections found via the internet, around which community can be found, built, and exist in that networked space. The internet, at its best, gives very disparate people ways to connect and support one another, and there’s certainly a feminist energy here that Nancy taps into in this work; it shows one person but the title implies many, and the talismanic nature of the work suggest another form of interconnectedness[4].

This is carried further with Anne Geard’s conversational action, which I was lucky enough to witness – this is a re-creation of a live work wherein Anne had a conversation with Brigitta Ozolins and Sally Rees. This was super interesting, but also problematic for me: I wonder if you can do these things again with genuine success. I see performance and live actions as experiments in art, and once the outcome is known, or has at least occurred, do we need to do it again, and what happens when we do? The work changes and becomes a ritual, which is by its nature something that we repeat, or at least could repeat. That’s fascinating, and it suggested to me that Invisible Power as a show was about the creation of ritual and transformative states.

Bliss Sandhu’s images of women in the thrall of what I think, I guess, are hand-held devices, are images people in a very common ritualised action we see a lot in this cultural moment, which has various names. The best known one is 'doomscrolling', but that’s layering this activity with negativity, and that may or may not be what Bliss is doing here; we could also suggest the people he shows are relaxing, or maybe we don’t even know completely, we’re just being shown a very contemporary ritualised activity wherein people (here all women) soak up information; it’s just that we do not know what is being watched.

It could be a streaming service, it could be a lecture, it could be pornography, it could be anything – we simply do not know, and it’s not intended for us to know - and the artist might not know anyway, and the artist is no way obligated to supply all the answers[5]. What we are seeing here is that captured moment where someone is almost out of their body, feeling their way through a very different, though no less real, space, gazing into a light that fills us with the unending cascade of information that is the internet.

Kerryn Fountain is more concerned with light than with ritual, although there is something ritualistic in the creation of her works, and all of her explorations of light and image are experimental in nature: a process is undertaken and there are a series of results that have a certain delicacy and strangeness. The process and the material are the work here: there are deeply subtle gradients that ebb and flow in a near-tidal sense across the various works here. The volume of work here does manage to communicate the experimental nature of the art – that is, the artist is undergoing a process where experiments are being conducted and what we see here is both the end result, and a by-product; the suggestion of slow mobility implied as you follow the art around.

Invisible Power examines light, ritual creation, the invocation and creation of power, and being subsumed by power. Power is a word with many meanings – it can refer to politics, economics and electricity; it can be good and bad, and it can be neither. I was left by this show wondering how you actually enter into dialogue with the multiplicity of such a vast topic, and where the ideas of power overlap and cause tension and friction. Power is also something we need to understand better, because the wielding of power in the world such as it is has great and terrible implications. I liked the direction this show was pointing in, by asking us to deeply consider what power is and how it might touch us, and how we can deal with it, but I also await the next step, because I feel like this question has been asked before too. We are shown problems and solutions, and the most potent juxtaposition was found between the work of Bliss Sandhu and Nancy Mauro-Flude: are we going to be zoned out consumers of an endless churn of distraction, watching looping fragments in a state of exhaustion, or are we able to attain some ability to be active and make connections, and find networks that grow genuine change?

[1] I am by no means the first person to note and there’s some awesome books about significant clothing items; I even own a book called The Black Leather Jacket by proto-punk writer Mick Farren, who is a fabulous weirdo.

[2] Fast fashion is absolutely something I do not know enough about, and I’d like to know a lot more about, but I know enough at this point to understand it as a tremendous issue that is bound deeply with global capitalism, climate degradation and human exploitation

[3] Public Enemy’s She Watch Channel Zero (found on the seminal hip hop album It Takes A Nation Of Millions to Hold Us Back) features a guitar squeal from Slayer’s Angel of Death (found on the seminal thrash metal album Reign In Blood). I love this as a cultural moment where highly influential bands kind of intersect, and it remains a primary moment of evidence for me about the sheer weight of context when it comes to sampling and collage – a Slayer sample brings Slayer, and the content of the song Angel of Death – about Nazi atrocity - into a critique of bad television content, and indeed, Fake News. Public Enemy do this knowingly, because they’re so smart and on point on this particular album it beggars belief; the whole album is a massive criticism of the US, and it’s not just the lyrical content – it’s every aspect the album was built from. Staggering. This kind of art is Noah’s cultural heritage, and he knows it and uses it.

[4] I sort of want to say coven, or coven-like, but that itself becomes a dominating image of women, and while I respond very positively to this, I am unsure if everyone does or wants to. Still, it’s important to see some groupings of anyone as opposed to dominant patriarchal cultures, and it’s probably alright to suggest that a lot of groupings of women that support each other to survive patriarchy, however they do this, are subversive just by existing.

[5] This is incredibly important to me: I do not think an artist has to have all the answers. I think that gaps in a work of art are a good thing, and that it is totally fine for an artist to say: I don’t know, what do you think? I think art that asks us questions, or suggests that we consider something, is great. I also don’t think art has to do that to be great; I just like it when it does, and I fully defend artists who suggest that the audience might think a bit about some things.

Make and Do: Interviews

The Make and Do website elves* have been working hard in the background, making this whole show run smoothly and be more accessible. We will be announcing some <Angels Sing> ~ NEW STUFF ~ </Angels Sing> around our July birthday celebrations and we've been changing some things up.

One is that our interviews (formerly the Make and Do podcast) now have their own special space on the website and we have moved audio hosting services (so if you were subscribed, you can unsubscribe - or do whatever, I'm not your mum).

There are currently two excellent interviews to listen to: Ricky Maynard and Victorian Vyvyan.

Stay tuned for more coming real soon!

*It's Pip.