Notes on paper towns and abandoned places

Janine Combes

MFA exhibition

Last day on Sunday 8th December at The Plimsoll Gallery, 10-2.

Amid the slow demands of life, I correct my posture: my shoulders and neck have been in wretched pain for days now; I have been using a chair that is wrong, and sitting hunched at my laptop, trying to write, hurting, failing. This is the second bad chair.

I push my shoulders back, straighten my neck. It’s an effort of will purely. It gives relief of a sort. I’m so exhausted and the room lies around me in fragments, with the run of the day – the tasks I do, in pieces, to keep domestic collapse at bay.

I am skiving off. It’s important though.

I must tell you a secret. It is urgent.

A couple of friends told me to get to the short-run MFA submission exhibition by Janine Combes. This rarely happens; it meant something was up. On Friday I had one appointment in the morning, then headed along to the Plimsoll Gallery.

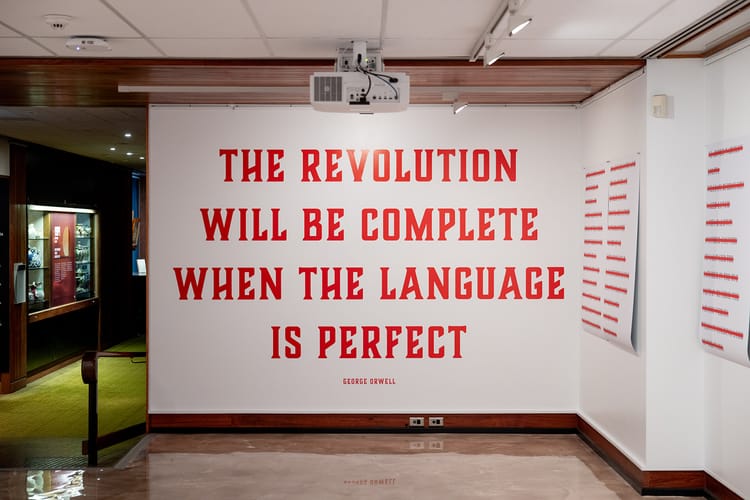

Janine is a jeweller. Her work is good, and stands out. She’s one of the bold contemporary jewellers who use unusual materials and works as much with history and politics as with fine metals and fine techniques. Janine uses words, and uses fragments. This exhibition is a result of a genuine and driven investigation that extrapolates with a strong logic from the work I’ve already seen into sculptural and installation works that are breathtaking.

What is history?

History is many things, and it is a subject for debate, and in a place where colonialism is a defining force, history is contentious, and can be a tool of politics and ideology. The dismantling and interrogating of a historically dominant colonial narrative is important work, and to do so, we return to the fragments that compose evidence and look at them again. Sometimes fragments are all we have to probe into history, and from them, the shards, broken and decayed, stolen and contested, we have some version of what the truth was or is. You have to honour the fragments. They are all we have, sometimes.

The Plimsoll Gallery is set dark, as if a haunted space. Some of the artwork here is in murky light, and it points to something critical: while there are many separate objects and works found here, the dark that creeps across everything and use of shadows at critical moments make the exhibition into one unifying installation. It is an attic we explore, where the water and weather has leaked in, and light spikes in shards to illuminate almost at random the selection of objects, the things.

Much is decaying and broken.

There is a table, set for a feast with goblets, that sits unattended and brutalised gently by time, the metal tarnished to green patina and stains.

There is a chair hung on barbed wire that dangles, sinister, from barbed wire. Barbed wire is a central thematic: used to divide land and denote ownership; to say this is mine, barbed wire is the essential colonial signifier. A barbed wire fence tells me that there is the violence of illegal seizure present, it denotes incarceration, violent conflict, and here, where a chair hangs, dangling and awkward, human agony.

This contrasts with the presence of button grass pods, which at times are attached to other structures of barbed wire, that look like unwearable jewellery. Buttongrass plains found in the highlands are the results of many generations of people undertaking cultural burning; the pods are a symbol of interaction as well, though not swathed in violence and dispossession.

The chair is disturbing and precise in its critique.

It’s like everything here though: Janine has collected objects that suggest history, then treated them so they take on the damage of aging while no one cared for them. They were abandoned and left to decay. Their story decays and changes with them, and the response they illicit is tinged with that change.

Janine is investigating history by making objects that resemble and denote history and absence.

The Plimsoll Gallery is dark, with shafts of light, and it’s an entire installation-based artwork, with many elements. It’s extremely well put together, and while I was struck again and again by individual set pieces, what really makes this succeed is the cohesion. Each work informs every other work, and you put the fragments together. There is a story here, but it is not one story: it is many fragments and shards of stories, all pulled together. The objects are made by a superb jeweller with a strong commercial practice, so everything is well-made and it all looks ‘good’, but it never looks too good, and the staining and tempering that exists across the show are amongst the most beautiful decay I’ve ever seen.

This is a stunning show; it’s surprising in a high degree, and reveals Janine Coombes as a superb artist who has, with this exhibition and her Masters work, has made a notable contribution to the ongoing dialogue about colonialism and the violence it bought.

It's on for one more day, and then it’s unlikely you will be able to see this work presented like this again. I urge you to attend; that’s why I banged out these words: I want people to see this.

Okay, I’ve told you my secret now.

I’m going to take some painkillers.