Notes on Apologue Isle (and other exhibitions)

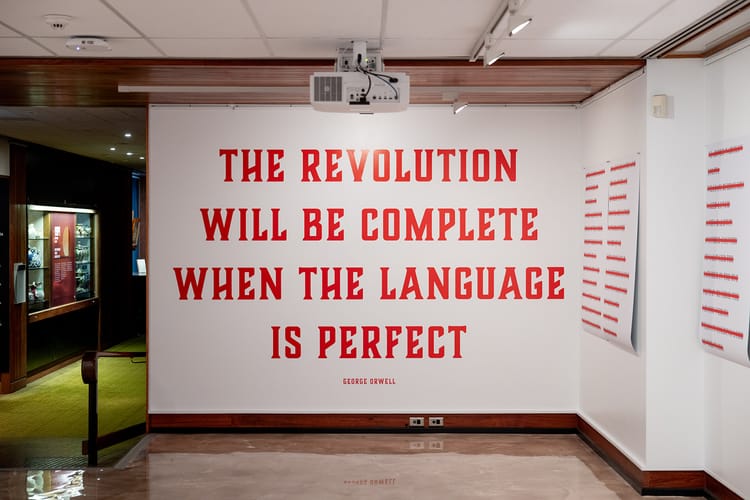

I have my interests and ways I see things, and regular readers will likely know what those things are by now to some extent. I see art as a number of fairly differing things, but probably, primarily as a form of communication. I think art is really good at communicating things that are not going to work quite so well with words. I’ve never found a really good way to put this, but words and language are, by their nature, somewhat generalised; we all have to understand what a word means for it to function as a word. Good poets do interesting things with combinations of words, but when an artist uses their art to communicate a feeling or concept specific to them, you get a unique expression, or you can get one, which is implied by the medium the artist uses: that something comes to you as a film means it comes with certain implied frameworks and meanings, and this is different to when something comes to you as a painting, or as whatever.

The medium itself is important, then there’s the content.

This is why I find some art utterly breathtaking, because somehow, I understand what someone means in a way that has been communicated without language. This is, when you consider it, quite remarkable, and good art is remarkable. Art is also incredible in that it can change over time, or it can change depending who sees it and how they see it.

So, a kind of communication. Which is reductive, but I think that art has to be reachable in some way first, for it do anything else. Art also does this other thing as an adjunct to that, which is it both reflects and shapes the needs and changes of a community, or more broadly, a society or culture. Art is a way we talk to each other that involves more than talking, that expands and enriches communication.

I watch art do this, and sometimes, something occurs that is quite remarkable[1].

This year, locally, (that is, in and around Nipaluna, where I see most of the art I see) something interesting happened and is still happening. This interesting thing was the presentation of art in various places and forms that shared an analogous crossover with ideas of folklore, or fable, or even fairytale. For example: Unfamiliar Familiars, which had lots of hints and gestures to new forms of story and lore; Edith Perrenot’s Wildlife Crossing, which addressed an idea of folklore and stories and how they can change and adapt; Ghost Mangoes and the Marching Antcestors,[sic] from siblings Georgia Lucy and Maille Kim, which was about personal lore and the making of story and how they felt a need to share their new narratives and fragments (I note that there’s a phenomenon where families or groups of people can have their own language and lore, and this show was an excellent example of how this can occur).

All three exhibitions moved conceptually around a notion of personal mythology, perhaps emerging from confronting events, be they personal or more about the complex times we live in, or both.

The above exhibitions had already occurred when Apalogue Isle opened. Art does not come out of nowhere and for all these exhibitions there’s been a lengthy development process undertaken and other things were happening in the artists' lives – so they incubate in very specific, personal circumstances, and yet we end up with four exhibitions all examining lore and storytelling in some form or another.

Apologue Isle was the most complex manifestation of this tendency, and it also seems to have had to longest process, the biggest budget and the most amount of people involved, but still – folklore, yarn, tale, fable, call it what you will, there’s been a lot of it this year.

I’m really struck by this. There does not seem to have been much overlap either, in terms of the artists involved; this is incredible when you consider the number of artists involved overall and the nature of the arts scene in Nipaluna (it’s not that big and there are many connections). This seems to indicate something: we live in cultural moment where the generation/creation of new folklore is something that needs to happen. I don’t know if any of the material I’ve mentioned actually will become that in a genuine sense, but the idea that stories are needed, and that people are generating them, from varied sources and in varied ways, does seem important and again, something that current culture requires[2].

Apologue Isle’s collection of narratives came from a few premises, notably that these tales would somehow be of Lutruwita, and that they would give voice to things that do not speak – which happens across the board in fairytale and myth everywhere and forever. Still, the notion that something we might call 'nature', or what are representatives of nature and the cosmos are given voice to comment and share seems important: What would a tree tell us?

There’s weather and fire and the sun and moon too, and all are given voice. I love this so very much. It’s just magical. And it’s also pertinent.

The stories, remarkably, are all really good and work incredibly well, but what I was more moved by was the act of creation, how it emerged from a collective, and how complex the presentation was, and, yet how it all seems really simple. The mechanics served the mesmerizing nature of the whole project. The stories, the actual core of the exhibition, work. They are also authentic – the stories from Palawa people are particularly potent[3].

I guess this strange world demands new stories to spark imagination and to aid navigation. Shared narrative, story and lore seem to be very human; there’s are as many of these are there all peoples in the world and there’s incredible old material around[4].

What is pertinent, though, about Apologue Isle in particular, is its attempt to talk to now in a way that has connection to older cultural modes[5] as well as to this moment. Some of the narratives are far more like contemporary fiction than they are traditional fable, and some sort of sit between. Whatever the delivery, everything worked amazingly well, and the initial vision, whatever that was, delivered something exceptional. I really must congratulate Andy Hutson.

That Apologue Isle seemed to be part of a greater, more complex moment and had these connections I have drawn (I hope not too tenuously), with other exhibitions, makes it all the more powerful. I really hope it tours, because it needs to be seen, because this need for story and the messages of new and old lore are not limited to Lutruwita by any means.

I need to add one more thing that I liked about this: in making the show, Andy Hutson built a community around his work. It’s probably almost too obvious to say this, but if Apologue Isle wanted to do something about the many things that are troubling the world right now, then the making of community, and demonstrating so strongly what can be achieved when a range of artists all work together, is a powerful statement.

[1] The most dramatic incidence of what I’m trying to note here in this meandering observation is the emergence of punk as a cultural phenomenon. What strikes me the most about punk music is the way it bubbles up from some sort of ferment in different global locations at about the same historical moment. There are explanations for this of course – the appearance of punk sounds in New York and London around the same time is understandable and even obvious – those cities are not so far apart in terms of cultural exchange, and shared a certain desperation in the mid-Seventies. However, it gets more interesting by far when you add Brisbane into the mix, and note that the Saints started forming in 1973, and crucially, release their first 7” record, I’m Stranded, before any of the UK punk bands. You can say that the Saints were listening to the same records as the people in New York and London, but that these people and bands all kick off in about 1974, then get records out in 1976, then basically alter popular music over the next twelve months is astonishing; and while I have no real proof of this, I think it’s because the music listening world needed something like punk to happen at that moment in history. There’s a lot more to this, but I think cultural need creates niches and artists fill them, and something artists are good (sometimes) at, is seeing the niches. This is not the only thing art does, but when you look at something like punk, and how it emerges in such disparate places, it’s worth wondering about how that happens because whatever else is going on, it’s not a coincidence.

[2] I can sort of speculate wildly about this, but I look at how utterly something like contemporary cinema has failed to provide us with stories recently. There’s a lot of movies that are involved with brands, like superheroes (all superheroes are BRANDS. Yes, I will fight you.) or games; the problem with these brands is that as stories they cannot end; the superhero will not die, and the game has to work in a certain way, and anything that becomes a franchise works against there being a story with an actual ending. We have so much ‘worldbuilding’ and ‘universes’ at this moment, and those things are damaging to narrative, so we are lacking story on some level, so people do what they have always done and make their own, which is a huge oversimplification, but tie that to the non-narrative content provided by social media (I’m so sorry but I had to) and maybe there’s something to this. I am not going to assert anything I can’t prove like ‘humans need stories’ but if you look at, oh, every damn culture that’s ever existed, geez we make up a lot of wild narratives. Also, books are consumer objects too, and the growth of fine expensive editions as commercial fetish objects is making my left eye twitch, and do not talk to me at all about fucking records. Records, not vinyls. Ahem.

[3] One of the stories, The Sun, The Moon and The Caterpillar, by Kartanya Maynard, is particularly wild because it’s about the sharing of lore and story across generations and noting this as part of what makes identity. It’s done really gently, but the story really moved me when I got it, because it suggests that this is what makes culture, and all the weird western stuff about blood is nowhere near as important as the connections made through the sharing of story. Other aspects are important of course, and I don’t want to downplay anything, but this story about the sharing of stories feels like the most astonishing analogy, and when you consider things like lore around fire management, which exists, the sheer importance of this ignored information becomes beyond crucial. I

[4] It will come as no surprise that I am hugely interested in traditional stories, folk tales, old fairy tales and so on. These stories have a rich resonance,

[5] The use of mechanical, moving things that are hand-built took me right back to a range of television that I watched as child. I recall seeing moving things and puppets, toys that came to life, stop motion animation and cut-outs on sticks, all of which seem to inform the aesthetic of Apalogue Isle. It gave me a rich glow of memory, and familiarity.