MAKE AND DO SEPTEMBER: I AM SO TIRED I MIGHT JUST DISSOLVE

What is it, this Late Capital world? Who on earth agreed to all of this? There is so much going down and I have to admit this insane wind slipstream has been driving me utterly insane. There’s a JG Ballard story, The Wind from Nowhere, that describes a terrifying wind that gets more and more intense, making civilisation impossible and plaguing people’s mental health. I have been thinking about that story a lot, as it describes something akin to climate breakdown, and notes a series of ways that people try to mitigate the situation – there’s a millionaire character with a private army who builds a pyramid, which seems very like some real-life individuals we currently have on this planet. It does feel quite apocalyptic and dystopian to me; I keep thinking a vast herd of triffids will come clattering over the hills.

There’s also a lot of life stuff going which I must admit has thrown me right out sync here, and I have been also suffering from a bizarre affliction where I write a thousand words about a show, read it back and discover it’s awful and doesn’t say what I was trying to say. This usually does not happen but it has been a lot, and I want to give all the people that read Make and Do something that’s worth reading, and this is more important than adherence to a self-imposed schedule, I think. Tell me if you disagree. Or agree. Or don’t mind either way.

Some other things: I have become completely obsessed with the astonishing podcast A History of Rock Music in 500 songs by Andrew Hickey. It’s a huge deep, deep dive into rock as a cultural force, and it is so in depth and granular it’s just ridiculous. The podcast begins in 1939 (!) with a song called Flying Home and is just now presenting a long dissection of the Rolling Stones song Sympathy for The Devil, which is absolutely astounding listening. I like the podcast because of the writing first and foremost, but also because the author brings a sharp, realistic view to rock’s characters, and makes zero excuses for the appalling behaviour exhibited – which is great, because the standard tactic in rock history has been to ignore or minimise the bad actors. It’s almost like a full revision of how we understand rock music, and the method used intensely useful – especially when I find myself wondering how I am going to deal with the bad actors of the art world, which I find myself doing on occasion (there’s still a podcast about Picasso coming, but it will not arrive until some other pressing life stuff is dealt with). Anyway, check out A History Of Rock Music in 500 songs; it gets better as it goes along – the episode on The Velvet Underground is particularly good, and it does mention the connections to people like La Monte Young. It’s also just a great way to do a complex history of the cultural impact of something like rock music, noting that there’s a canon, that there’s a reason for a canon, but also noting the problems of a canon, and what a canon buries and leaves out. This is something that also happens and needs to happen more for visual art and possibly every single form of cultural production we have; understanding how the existence of canons serves capitalism might be useful.

Kelly Nefer, who did a neat show at the Rosny Schoolhouse has made a Just Us Journal, which is very swank publication filled with politics, art, rants and activist stuff, and I love it and you should track it down. They have an Instagram so try there. This kind of publication has become intensely rare, and it’s wonderful to see it.

The State Library Fellowships are open again – there’s a bunch of categories so look here and get all the information. It’s all about working with the Library and Archive collections – if your projected is accepted you get inducted and a huge resource is yours to play with, and make something special. It’s aimed at people who will actively use and visit the library, so if you live in Nipaluna, this one is for you – get in there! Applications close on the 4th of October so do not sleep on this. Libraries and archival art are the bomb.

I also want to tell you all to get into Nipaluna/Hobart itself and go look at the latest Graff in Bidencope’s Lane. There is, as usual a lot of variety and a lot of stuff to look at, and I love how this place evolves. In particular, long-lasting Graff survivor Topks1 has re-done his mural that counts the number of children murdered in Gaza; the original was painted over (it’s Graff and it will always be that way, and it has to be or it is not Graff; it’s a fluid medium) but it has re-appeared even stronger; with the number of dead children being updated by the artist. I think this is powerful work; it’s certainly one of the most on point things any local artist has done to talk about Gaza, and it points to something special about street art – it can and does react quickly and share the news of the moment, and its’s fluid, ever changing nature allows it to do that. It would be nice if Tokpsk1 was given access to another wall for this work as well. It would not hurt Contemporary Art Tasmania to reach out and give one of the most persistent street artists this city has produced a go at the CAT courtyard.

There’s abit coming about the fabulous Jo Chew show as well, but I need to proof this so give me a minute, and don’t forget to check out all the upcoming stuff for October. I will also tease a special Make and Do live event on the horizon, which will involve my obsession with a particular artpunkpop band and the idea of listening to records and talking about them.

Alrighty groovers, here is a ridiculously long look at some recent stuff.

Thanks everyone. I could not do this without you.

THE COMPASS WE MADE WITH CARDBOARD AND GLUE, THE FORT WE MADE UNDER THE TABLE AND ALL THE TROLLS WE TRICKED

Notes about Wildlife Crossing, folklore and other tales

Edith Perrenot at The Rosny Schoolhouse

and

Ghost Mangoes and The Marchin Antcestors

Maile Kim and Georgia Lucy at Good Grief

Sometimes you see art that does a beautiful job of making tiny myths and telling stories, and over the month of August, two such things popped up and the same moment. Coincidence is coincidence, but it was fairly amazing to note that two rather differing takes of what I saw as a similar kind of activity emerged at roughly the same moment. We got Wild Life Crossing, folklore and other tales from Edith Perrenot at the Rosny Schoolhouse, while over at Good Grief, Georgia Lucy and her sister Maile Kim (who sometimes play music together as Those Bloody Ingalls) gave us Ghost Mangoes and The Marching Antcestors (yes, that is not a spelling error). Both shows, in differing ways, featured the ordinary domestic otherworldly that we can encounter in our lives, and both exhibitions shared narratives that were composed of profoundly personal elements and beliefs. They also have performance components I missed, but I saw some pictures and chatted to people who were down with it all.

It struck me to consider much larger questions, about folklore and fairy tale, about the strange things that happen in a quite normal way at the border of life and death, and how things like folklore and the shared hallucinations of art and craft and magic sometimes exist to help us navigate the hard things and the strange, raw moments of our lives. We experience loss, and we make art out of it, and if we get it right, other people find something comforting in what we share.

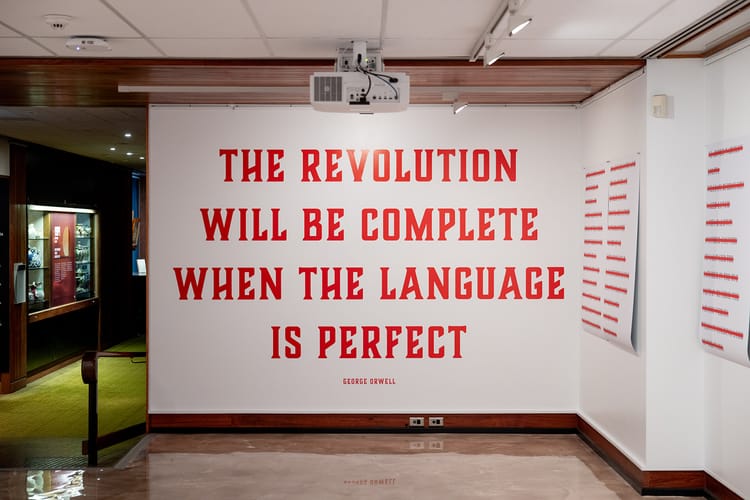

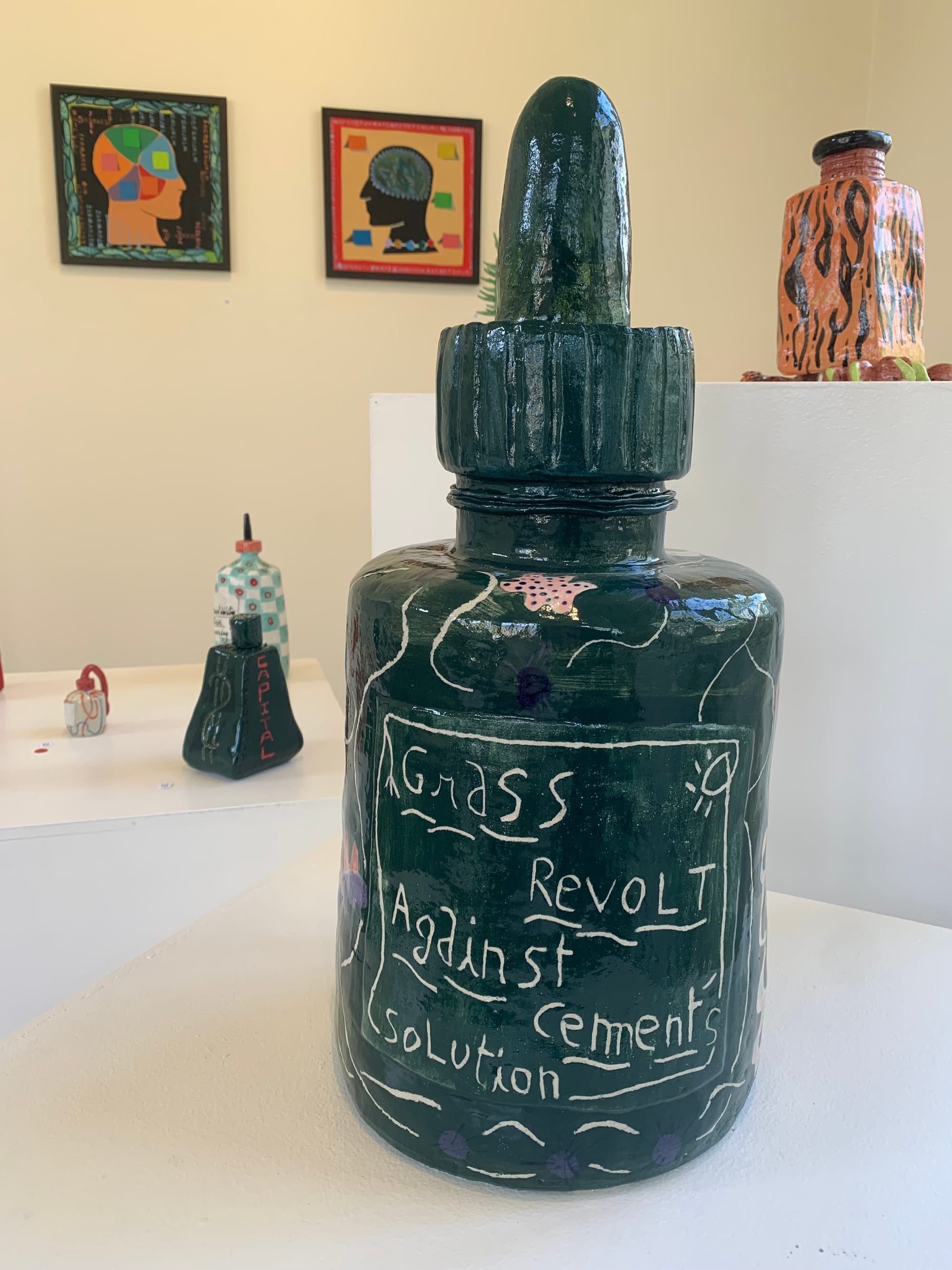

Edith Perrenot built some new folklore, and it was sort of amazing. Edith has a strong aesthetic that relishes in appearing handmade and immediate: no matter what medium she uses, all the work looks like Things Edith Made; she has a distinct style. There’s a selection of ceramic objects that call into mind an old apothecary, where tinctures are available for all manner of ills – but Edith made these wryly into comments on culture, naming them as things like Grass Revolt Against Cement Solution. There were also some installation-style works, some paintings, some things that looked like ceremonial masks, and a huge soft chain stuffed with garlic and other herbs. I’ll start with the chain, but everything here was sort of linked up (link, chain, that was an accident, but it works well for what I’m trying to indicate here, I hope), and managed to be about Edith and how she navigates the experience of moving to Lutruwita/Tasmania from France, and how she brings her mythology and folklore to this new place, which is actually very old, and has its own lore.

Edith’s work made a strong issue of respecting and acknowledging that tension. The chain soft sculpture did this very well: it turned out to have its origins in the tale of the Four Thieves Vinegar, which dates from the Plague in Europe. The vinegar was an herbal prevention for catching the plague, named after Four Thieves who either robbed plague victims, or who were forced to bury plague victims, and used this special vinegar to not get sick. Edith wanted to use this story, but recognised the problem of simply shifting it from European legend to this place; so she adapted the ingredients and made the decision to gather everything by hand herself, from local sources, and incorporating locally originating plants. She even decided to pilfer some of this stuff, casting herself now as the Fifth Thief, updating and shifting the original story.

Folklore changes and adapts over time; this is how it can stay relevant. Edith’s decision to adapt effectively creates a new story, and brings the idea of a kind of magical defence against a pandemic into the now. I’ve no idea if Edith’s concoctions might really work, but the symbolism is elegant, and while I mention pandemics, there are many other plagues and worries we have right now; Edith’s herbal stuffed chain exists as a gesture towards finding new cures for a range of ills by using what we learn, what we might find and opening our eyes (and minds, and hearts) to what other traditions and lores might reveal, if we actually pay attention. There are moments like this throughout Wild Life Crossing, folklore and other tales, alongside more personal fragments, some scientific debate about carnivorous plants, the strange tradition of hiding a shoe in a wall for magical purposes, and a huge collection of mallow flowers, that are native to Palestine. The presence of these plants directly indicates the genocide occurring right now, and the hope that the people of Palestine will have freedom and safety. I learned here that Mallow flowers are used as food and medicine in Palestine, and have been for centuries, and that the state of Israel has made foraging for wild plants illegal. The symbolism of these flowers bursting from a chain is obvious and necessary; and this work is composed of lore that addresses a very real monstrosity happening in our world right now. Edith’s work examines herself and her place but reaches outward with empathy and compassion.

Maile and Georgia’s inhabitation of Good Grief in August was also filled with personal myth, but it centred around one event and the days leading up to it: the passing of their dad, who was terminally ill and decided to find a day for his own life to draw to a close. This is obviously heavy, and I want to acknowledge how bold it felt for these people to share that profound navigation and to make something out of it. I was ushered into the space by Maile one wet evening, and told the story – how the mango tree next door, that had never borne fruit, had finally been pruned and was now heavy with produce, and it was something Dad could eat; how ants invaded the house and seemed not interested in food but a stash of USBs filled with precious digital memories of family life; how a ring with DAD emblazoned on it was dug up in the yard while a task was being performed; and there fireworks, and songs, and an old Helmet t-shirt that Dad decided he would wear when the moment came. The shirt depicted a human greeting an alien, and it seemed right for someone who had decided to leave the planet. Maile and Georgia made a statue of this, and it was weird and sweet.

This was powerful enough to even hear about, but the act of sharing it, and making a whole lot of symbolic art, and filling the gallery with song and memory was, well, pretty wild. Lighting the gallery with glowing mango lanterns and making improvisational music that emphasised play and community is a glorious idea – and it makes for a great story. So too did all the stories I got told about the incongruous occurrences that emerged as the family gathered together to be with Dad and aid his journey. I got a first-hand rendition from Maile, and I felt lucky to share it, because these moments are when people are most alive, even near to death. I can imagine people sharing the details, and them being told, and told again, and taking their own shape, as these things do. I wish I’d seen more of this, but I also got my own version, just for me, which was unbelievably generous, so thanks Maile. You’re a legend.

This isn’t very like art criticism at this point, but let me tease this out for you: I think stories, and fairy tales, and folklore are deeply important, and that while we have a glorious backlog of material, we all know, that material got written down, and it became problematic, because it became static. As Edith Perrenot recognises, when stories and lore are re-plated in a new location they are taken to by the movement of people, they become oppressive. They also lose their fluid nature, and that actually removes what it is that makes them important: stories change as they go along, and the good ones meet the needs of the times they merge into. This does get recognised: when Angela Carter gave us The Bloody Chamber[1] in 1979, she used the essence of traditional stories to make new ones that addressed the concerns of the era.

Maile and Georgia lived a story and made it into something that is still forming and may never really be locked into a particular shape, but that is no bad thing; it allows their real experience to be weird and beautiful, and for it to be shared and still be theirs. What Ghost Mangoes did for me, at least, was affirm that odd things happen, and that those echoes that we call memories or ghosts or déjà vu are things that are normal, in that many of us do experience glitches or whatever we chose to call the shifts of the real and unreal.

I mean – both these exhibitions were on at roughly the same time, both dealt with personal experience, both filtered understanding through the creation of kinds of folklore, and both featured art that was very much derived from making things that feature your own experience and knowledge as actual material, symbolic and other wise.

I’m sure that was just a coincidence and there was absolutely nothing unusual going on there.

NOTES ON WITH WATER OVER TIME

Harrison Bowe

Despard Gallery

As I was leaving Harrison Bowes’ show at Despard, I noticed the show’s title had been painted low down on a wall near the entrance, in a sort of cursive script. It looks like a tag, I thought. By tag I mean those parts of street art and graffiti culture that get the most flak from people who are outside of street art and graffiti culture, and are often likened to territorial pissing by dogs, or get called ugly, or just denounced as pointless. I do understand that take, and its even sort of valid, but I see tags as someone with absolutely no power or position in a culture stating they are in fact here, they exist, that they have no choice but to make space in the only way they can, which is making this quick mark that proclaims they will not shut up and lie down.

I don’t think Harrison Bowe is doing that exactly when he writes a show title on wall, but it is a slightly unusual thing for an artist to do (although I’ve seen it before). It fits though, as Harrison Bowe is a somewhat unusual artist, and a good one. I’m not going to write about his art as such here; what I am going to do though is consider something I see in his work.

I got lucky and saw some very early video work by Bowe that was very much understandable as a documentation of him making street art, or a version of it – he’s moving, almost like a dancer, painting abstractions directly onto a wall. The energy is astonishing, and it fits with what his work turned into, and why what he’s doing when he paints landscapes seems – well, unusual.

You sort have to know some of Harrison’s story, but in his landscape work he is not so much looking at an astonishing view in a remote location, as he is capturing the moment when he himself arrives at the place he paints and breathes in really being there.

I do not know if that actually makes sense, but there’s something really physical at play in what the work is doing, as the movement of the artists body is an essential element in making the art. This takes in not just painting but the act of going to a place, walking, drifting down a river, being there, immersed.

Street art is very much about the moment of the action. Street art is fast by its very nature – if you are doing something illegal, you cannot take time over it, you have to have a plan, and a level of confidence. You cannot pontificate. You have to get stuck in. You need the picture in your head and you need to just do it and get out; it’s laced with adrenaline. You need to accept your work is ephemeral, and that the real thrill is in making it; the important thing is the moment of creation.

Now, it’s obvious that Harrison Bowe’s art is not totally about that moment and nothing else, but I can see a very obvious parallel here an approach to street art and graffiti, and the real energy you can see in Bowe’s work that makes it what it is.

He works with palette knives and mixes beeswax with his oils; this again suggests physicality and movement in how the work comes together. Harrison has been using some big canvases; this would be natural for someone who has taken on a bare wall. All the of the seventeen works in this show were made this year, and Harrison has shown a few other things recently – he clearly works at notable pace.

I note this largely because I think it’s interesting, but also because, while Bowe does fit into a tradition of landscape painting, he also brings something else with him, and it might be one of the reasons his work has the qualities it does.

Of course this is just me, and I am extrapolating a lot out of something that looks a bit like a tag, but there’s something about Harrison’s work that really invites speculation. I see a lot of landscape art, and I always will, and this work really stands out for me, and I am greatly enjoying working out why that is – and the way the work really invites that. This is my baseline, really – does a work of art, any work of art at all, invite me to consider it more, to find something in it that moves me in some way? Does it invoke thought, spur me to analysis?

If it does that’s a really good start. I guess I want engagement, and this art really engages me, in a way a lot of other landscape work just doesn’t. This is something I have to work out, and that’s why I do any of this at all. I also have to note that I see or feel the influence of a street art practice due to my own interests, which in particular here is to question the idea of a traditional lineage or canon in art, and the way that there’s clearly something different about Harrison’s art that makes it so compelling to me. It also means something that I find this total level of personal fascination with an example of a form I traditionally have issues with.

USING FICTION AS SCALPEL: NOTES AROUND SITE

Eloise Daintree, Selena De Carvalho, George Kennedy, Amber Koroluk-Stephenson, Mary Scott, Nunami Sculthorpe-Green, Brigita Ozolins, Angus Thornett

Curated by Jade Irvine

Various Locations around Richmond, Tasmania

7 September – 6 October

I can’t quite recall the last time I saw something quite like this project. SITE, a curated – what? What is this? It’s not like a standard exhibition; it’s more like a collection of investigations and reactions to the historic town of Richmond; it’s not just dotting a bunch of unrelated art that just sits awkwardly about the environs. It feels like the place came first, and the artists thought long and hard about what they could do to say something about Richmond. I’m unsure of what the curator, Jade Irvine did as a process to find the crew, but SITE features some excellent artists, and the work that emerged is uniformly really good, and it all sort of worked together. Cohesion is about the hardest thing to make occur in anything that features a number of artists; here nothing felt awkward or out place at all.

The most obvious work here is Blind Sight from Brigitta Ozolins. Brigitta has created literal rose coloured spectacles, very large ones, and placed them around the place, looking, if you will, at what we might say are ‘significant bits’ of Richmond. Richmond seems to mostly exist as tourist destination these days, and it has some historically significant structures that are essential to making the town what it is, in its current incarnation as a destination for those seeking leisure and informed distraction. One of these is the Richmond Bridge, which is exactly the sort of structure that looks great on a postcard or a nice mug. The bridge is pretty, and it’s interesting, and Brigitta suggests we see it through a particular set of lenses.

This is where SITE gets interesting. It’s not a great leap to discuss how the bridge was actually built, which was using convict labour, like everything was in that era (about 1823). The sandstone the bridge was quarried at Butcher’s Hill, which overlooks Richmond, and hauled back by ‘hand cart[2]’; It was a huge amount of complex work to make. It is historically significant in terms of its age and engineering, but it also is the key to getting to the entire eastern regions of the Island – this was, until the Sorrell Causeway was constructed in 1872, how the region was colonised. What you see when you see the bridge is the process of colonisation in action. It’s still a beautiful bit of construction, but it has a wider historical context, and that narrative is a lot more complex, and dark. We look at the bridge, and we are sort of distracted by the bridge from the bridge’s purpose. Look again.

This kind of work is very much what SITE does; the art suggests you look again, find a new context, take in the notion of a far more complex and even problematic narrative. Amber Koroluk-Stephenson does this neatly over at the Richmond Gaol. Convergence utilises surfaces and patterns and the ideas of construction being undertaken. This shifts Richmond itself; the place seems to be somewhat still in time, and not given a context[3]; yet the presence of a gaol probably means that this is where the convicts who constructed the bridge, and every other building from that time in the town lived; it’s the home of the people who built the place by hand, and were slave labour[4]. Amber suggests active and ongoing work in the past, and suggests that another form of construction is being utilised now.

It is very hard to know who these convicts were, and how they lived and died, and what their lives where even like. The evidence is there when I consider the size of one segment of the Richmond Bridge – how did this get moved? Where they terribly young and vulnerable, barely educated and not given adequate food? What abuses and traumas might they have suffered? We don’t really know, but we also sort of do, and it’s unavoidable, even be it dark and shadow-laden.

This is the point though, if I might pause and step back.

Studying history is important, and studying it well is a great skill. But it has limitations, which are that you need evidence, and proof, and you can point with history, but you cannot bring out the emotional resonances and overtones so much.

This is where art is useful. Art can bridge gaps. It cannot replace history but it can allow us to look at the history we have with more empathy, and with more of a critical eye – which is what the SITE project seems to be interested in; SITE wants to present a more complex, richer view of Richmond as a history laced location. I’d consider this useful, because what we have now to visit and have lunch in is nice enough, but it’s also something of a vacuous veneer. Nice sandstone buildings are great, but I find myself being more interested in the stories of the people who inhabited them, how many of them were pubs (it seems quite a number were, but that’s colonial settlement for you), and what went on in and around them. I’m personally far more interested, say, in how average people existed in a place like this, some two hundred years past, than I am in the tides and fortunes of politics. We know plenty about big people. They build statues of themselves. They make sure we know.

This kind of story is one Angus Thornett manages to tell well. I was really only slightly aware of his output as a writer and storyteller before I encountered his Richmond Revisited effort, and his measured pace drew me in; he presents useful factual morsels that served to create a larger implication about Richmond, and more broadly about the colonial era; these he led me to yet, did not spell stuff out or create assumption, more gesturing to an area of thought. He spoke, in one instance, about the prevalence of male violence and the low numbers of women in the colony. This has wide and worrisome potential in many ways, but Angus led me to a place without straying beyond evidence – this is good technique for a writer of history. He’s an interesting inclusion in SITE as well; no matter how you might feel about his style, his presence and input indicate a strong desire on the part of the curator to make an art experience that truly talks to the location, to Richmond and its history. Angus’s presence makes SITE different, and I have to note it – good move. I am aware of the potential presence of the Usual Suspects in art exhibitions, and for the most part artists get invited to these things because they are good artists, but you can also tell when a curator has to some extent phoned it in; Jade Irvine really did not do this.

Selena De Carvalho is important here too. Her art is always tinged with activism, with a strong politic, and with evocative nuance. I didn’t get to go on her walk but I did listen to her words that guide you through a version of Richmond, and I can’t underline enough how much I was engrossed by the sheer poetic structure of this work. Selena uses weird[5] stuff, she hints at herbal traditions, hidden queer spaces and the innate subversion of these existing, and generally presents a differing vision. I found my attention drawn to the way the space of Richmond had been transformed into a strange transplanted avatar of the UK – all the introduced plants[6] that fill out the central part of the town. We don’t really look at plants as part of the colonial project, but they are integral, from the cosmetic transformation of planting decorative plants shipped over from the UK to the devastating bludgeon of large-scale agriculture. This work reminded me that much of this place looked totally different, and that what I have always seen as bare hills were once probably covered in forests. Colonisers bring animals, they bring plants, and these things change a place in deeply integral ways.

A huge change was the expulsion of the mumarimina people from the region. Prior to this exhibition, I have seen very, very little, if any, acknowledgment of the people from whom the region was violently stolen. It seems appropriate that Nunami Sculthorpe-Green has inhabited the Richmond court house with images of warriors and resisters to colonisation, but there’s also a huge swathe of paper covered in rubbings of traditional stone tools, the images created with hand-made pigment chalks gathered by the artist. I’m not sure if these art materials were specifically gathered in the area, but there’s something defiant in the idea that despite all the changes, these materials can still be found; the tools to make art and story and narrative are still here. This installation work really succeeds because it’s quite direct, it presents the Aboriginal narrative of resistance. That it does so in a building made by convict labour that represents the imposition of colonial law might be the strongest point the work makes. I thought of the recent statements made by Jim Puralia Meenamata Everett in relation to the law in particular; that he does not recognise the colonial justice system and that he stands in his own sovereignty. Nunami’s work is not backward looking; it is about now, and underlines the presence and impact of history, and how history is ongoing, and not set in stone, refuting the oft-used dismissal of Aboriginal people that all issues exist ‘in the past’ – well yeah, but they are also right here, right now, and happening. The past is not another country, it is this one, and a lot of stuff has been sort of ignored and erased and stepped over, despite it still being there.

Mary Scott did something that has parallels with Nunami’s work just up the road (well everything in a small town is just up the road) – Mary utilised charcoal and found clothing items to transform the now-disused Richmond Bakery (which ceased operations in 1984). Mary’s installation, onethingintoanother is incredible; she has covered interior walls with striking, eerily gorgeous images of people and in particular, children. These images of faces are intense and mesmerising, and drenched with emotion: I stare into the larger-than-life eyes and there is haunting. Mary has haunted this space with memory, with the idea that people were here and they suffered and felt loss, felt isolation, and were treated with cruelty – and we do not know that in provable fact, and this is not what is stated, but what else is there to think? What else do we need? It’s interesting how that lack of historically relevant proof can be potentially weaponised to deny an understanding, and how history is written and controlled by those who can actually write. The people denied that opportunity become silenced.

I do not actually know what Mary Scott was intending – but I know what I felt, and this work of hers is so emotionally rich. It is charged with human feeling, and its wordless subjects seem to gaze from a range of pasts where they were buried by their circumstances, reduced to statistics or just lost, leaving only the merest traces, here suggested by shoes shrouded by dust.

Is there anything that suggests time and loss more than gathered dust?

There’s so much here unsaid, and this is the point: we know at least the shapes of what happened in these old colonial spaces. We are provided with enough information. There’s silent trauma that is buried, in time and dust, but it has not vanished. It never goes away.

Mary’s work is exceptional, and provided me with an emotional core to SITE. It was pitched just right, and has, more than any other work, stayed in my mind.

George Kennedy’s art also inhabits a building – St Luke’s Anglican. George’s work is some rather lovely drawing on a big roll of paper – big inky-black lines that capture visual fragments that take a wander around Richmond. This work is rough mapping of wandering, and explores the way people and animals make little short cuts and paths for themselves in a place. George has made such a map, symbolic and derived from his own mapping of the area. It seems appropriate that you can (and should) walk on the work yourself, as it sits in the church aisle. It’s a map that becomes a trail itself and I like the way George knew to not make the work more important that what it depicts. There’s not set path, you make your own: notice what you notice and follow the indications.

I had to leave Eloise Daintree to now because Eloise’s celebration of local dogs – Dogs of the ‘Mond – makes a really useful shift. Eloise lived in Richmond, and walked a dog around, as you do. When you do this, you meet other dogs, you have dog chats about dog carrying on and tell dog jokes. It’s a warm and simple kind of interaction that celebrates the community as a good spot to wander about – and it makes another map of Richmond, a dog map of places to sniff and get excited about. Placing small, subtle stickers on bins suggests a bit of marking of territory, a sending of a tiny signal and a bit of gentle sharing. Eloise is importantly upbeat, like George Kennedy’s work – and they provided me with a lovely counterbalance that made Richmond and SITE more complex and richer, and made the whole project spread out more.

Again and again, I have been told you can’t change history. I understand this now as people defending an interpretation of historical evidence that suits an ideological position, and actually, you can present another interpretation. This is not changing what happened in place; it is changing how what happened is interpreted. It might be the case that we are in a historical moment in Lutruwita/Tasmania where the idea that colonisation was largely a positive historical event is being interpreted in a differing way. When someone suggest you cannot remove a statue, and does everything that they can to stop it, they are not defending history; they are defending an ideological position that a particular interpretation of history serves.

I don’t think that Jade Irvine actually came to SITE with an ideological agenda, though, I should be clear. It’s pretty obvious indeed that she did not, because the stories the art gathered here tell do not truly sit comfortably with each other – there are overlaps and takes and interpretations, and investigations of the related institutions of incarceration and injustice, but what there is not is an imposed thesis. That would have been a wrong move, I feel – I don’t think you can quite tie all these very differing works together in a neat manner, and I don’t really want to; indeed, I am pretty sure that would not even work all that well. Instead, we get a number of very differing works that present an interaction with Richmond as a place and a site for history that essentially suggest looking and thinking past what is presented, revealing a complex place that acts as something of historical microcosm, that people also live and work in, and visit and enjoy. A lot happened in Richmond, and looking at it in new ways is rewarding and even necessary; history is a fluid thing and not locked down; how we understand then can inform what we do now and to my mind, makes Richmond a lot more interesting.

[1] The Bloody Chamber is a really good book, and one that means something. It’s about sex, it’s feminist, it features writing that writhes with sex and bites with feral terror, and it’s now a bit dated, but you should really read it. Just do so with eyes wide open.

[2] I cannot find a picture or description of a genuine 1820s hand cart that was used for hauling sandstone down a hill. The closest things I found have two wheels and would have been challenging to haul chunks of anything with, let along sandstone.

[3] It’s a place I have to say I find ever so slightly odd. I think it reminds me of a creepy English Village I recall from watching a TV show called Children of The Stones, which was set in England, in a village inside a stone circle. This show was utterly terrifying, had the most intense theme music I’ve ever experienced and left me with a life-long suspicion of small colonial hamlets.

[4] Again, not new, but the whole system of transportation seems to be a system whereby cheap labour was arranged by enslaving the lower classes, and this enabled the whole colony to be built and for extractive businesses to get underway, and for substantial profit to be made. I’m not particularly fond of how this whole system was dressed up as giving the convicts another chance and a better life in a new country. Of course some of them did manage to extract themselves from the cyclic poverty and become mobile. But I have no idea how many people did that but I am willing to bet it was not all that many at all.

[5] Weird as in Wyrd; the work has that a witchy overtone that can very easily be overstated and become totally trite. That’s not at all the case here.

[6] I have become, since I worked with Jack Robert-Tissot on his exhibition at Good Grief, about plants and introduced species and the issues around such things, somewhat obsessed with the tussling for space between the introduced vegetation and that which was here before white people came. Selena hits on a few useful things in her piece, but this is a space that could be strongly investigated by other artists. Weeds are an issue, and plants are sort of unstoppable, and there’s a lot of knowledge we have lost, a lot that is held close by the first peoples of the world, and these things seem ripe for investigation. I sort of wish I could do this, but it’s a vast undertaking.