Notes on toppled statues and glass houses | May 2024

Yes, I know it’s June.

I got eaten by the deadline monster, then I recalled I was the deadline monster, so with a couple of deft manoeuvres I un-ate myself and decided we could be, a bit, you know, tardy.

So here’s some comment on some art in May and I hope you find it useful or engaging in some manner. May was busy for art and for me and for Make and Do, and there a few irons in the fire for some slightly different stuff, although writing about art in Lutruwita will remain at the core of what we do – and here it is.

We are nearly one year old, and we’re amazed at how many of you have joined us in this experiment, and in particular all the bits of support we have received.

The impact of our initial support from Art Tasmania cannot be over-estimated, so thanks so much for getting us going, and to all the people who keep us going.

Art is a community, and that’s incredible.

ART NOTES

There was a LOT on in the last few weeks and I wanted to note some shows. I had some public appearances opening a few things – which was awesome fun and I was incredibly happy to be asked out to play/read. One was Up and Coming at Handmark, which was a huge selection of emerging artists, including a few people I’d been noticing around the traps. I had a blast speaking at the opening – which was just chockers, and had a feeling – like there was a vibrant art scene, which I guess there is! It was just great to see this show at a space in Salamanca. Giving new artists a 'break' of any kind is crucial to sustaining the local arts scene, so Handmark did a cool thing there, and I was happy to be part of it.

I wrote some catalogue essays too.

One was for the terrific Michaye Boulter whose work Atmospheres is still at Devonport Regional Gallery until June 10th. And, for those in the South, you’ll be able to catch the show at Bett Gallery in July.

The other essay was for the most excellent Jack Robert-Tissot who has been obsessed with plants and neglect and weeds and a whole lot of other things that exist at edges – the parts of our local environment where weeds thrive in concert with the indigenous flora. This was at Good Grief and was just excellent fun to write about and open. There’s a really good catalogue Jack made that I had my bit in, with shiny paper and everything. It was great to be involved in a show that had an original take on contemporary dystopia[1] – Jack is a pretty original thinker. He’ll do more, so you know, check it all out as it emerges.

Next door to Jack at Good Grief was a belter of a thing by Reece Aaron Nicolaou, which was another take on Dystopia (as well it might be), sort of. It’s like a Fantasy was a slow burn of a show that I didn’t quite seize in the first instance. Reece is looking at a few things, one being the idea of water – there’s multiple reference to an oasis – more as a concept than a real thing, although that’s in play as well. I couldn’t escape either the notion of The OASIS from Ready Player One, which I didn’t really like at all, but had a cultural impact (the book sold well and the film was seen by many, and seems to be churning away on streaming services). This serves some use if we want to consider how far the practice of 'making lists', and claiming these, as narrative has permeated the cultural framework (Stranger Things, anyone?). Reece is playing with a number of multiple meanings for water – water as sustenance, water as a symbol, water as a product (he uses images of bottled water and images of liquid containers): an oasis also implies a desert, which has little water, little sustenance and is yet filled with life that adapts to it. Humans can do this too, but it’s complex and challenging, and relies on deep information to tell you where to find water – this is something some indigenous cultures build into their song and story and map making, which consumer culture replaces with lists and then attempts to sell us essential sustenance.

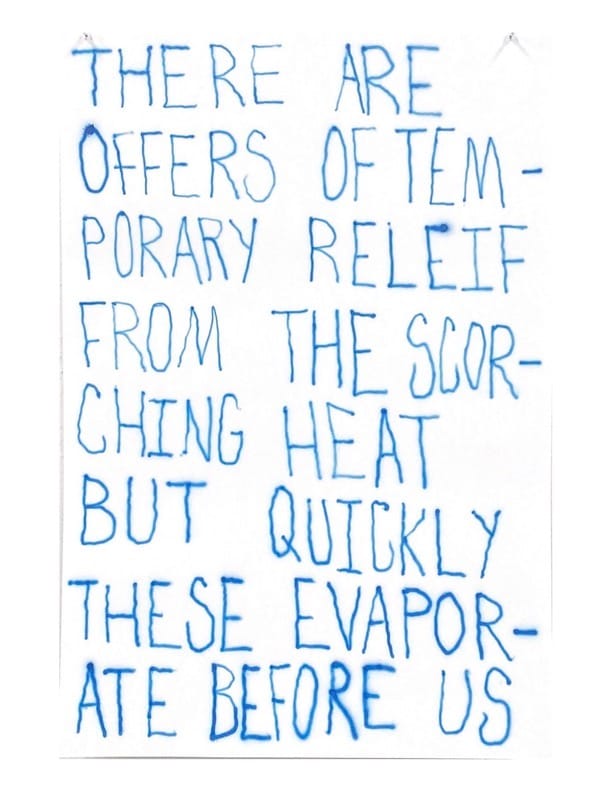

Reece included some images entirely of words[2] which also explore deserts in a more metaphorical state, alongside ideas of reality and consumption. The world we live in now is like a dystopian novella, but it’s really real – Reece seems to be asking us to consider the actual environment we live in rather than escaping into another fantasy, or pretending that we’re living in act two of a three act structure where everything gets comfortably resolved. Reece offers no resolution, but does suggest there are real issues here.

What I really liked though, was the whole aesthetic at play here. We see plenty of painting (and though there’s nothing wrong with that at all), so an artist who makes video installations with a dollop of Reject-Shop camp is going to stand out, and it’s especially gratifying to see an artist taking aim at a culture of consumption without making objects for the art market.

Another show I need to mention: Glasshouse- somewhere between underground cables and overhead flights, a collaboration from Nani Graddon and Marguerite Carson. This was a beautiful subtle, layered, inhabitation of the Rosny Schoolhouse Gallery. I really like the Schoolhouse; it’s a challenging space to use though, given its gorgeous windows, and it’s always fascinating to see how artists manage this. I believe it best suited to installation and sculpture, although I’ve seen plenty of excellent painting exhibitions there. Glasshouse was mostly sculpture and installation, so I found it really played out well in the space. The artists installed clear corrugated roofing plastic in the ceiling, gorgeously playing with the light – so much of this show was about light and how we perceive it. A glasshouse is ostensibly for growing food in, but it’s also an aesthetic structure that seems skeletal. Glasshouses have their origins in the Northern hemisphere and have in some cases become astonishingly elaborate, massively ornate structures. The structure in this exhibition was more modest; there was no glass but there was honeycomb in one panel and some delicate fern collage prints in another. Ferns and bees are things we have had around us for a terribly long time now (the practice of beekeeping is somewhere around ten thousand years old) and are replete with myth and superstition. Some of these tales are investigated in a publication that comes as essential part of this exhibition. I can be wary of such things, as I can be wary of artists statements – I want to find my own way into any art and not be given a proscriptive set of instructions on what the art ‘means’. The stitched booklet didn’t do that at all though – rather it becomes an important art object in itself, filled with musings and questions that just made all the work here more poignant.

There were also glass bricks, images of elaborate cut glass bottles, casts of small plant containers arranged in a corner that resembled an archaeological excavation of an ancient city, or sandcastles, or both. There was an overall feel of play and investigation with this show – what is revealed when we place objects into dialogue with each other? This sort of investigative art that takes disparate elements and creates work from the interplay is possibly not seen enough locally; it interests me a lot because of the archly conceptual nature of these strategies, and because I really like the idea of art that takes objects and a constellation of object and image that have something to do with light, architecture, gardens and growth. There’s a loop here: plants need light and heat, artificial structures created by humanity can both nurture and contain (control) plants and bees, we grow seedlings and we place them in greenhouses. Next to the practical aspect, there’s an investigation of all the forms and strategies we have borrowed from nature, which we alternately admire, stylise and control.

The introduction of other forms derived from nature, like ferns and honeycombs, serves to expand the inquiry and stretch it something else: what is to control nature? To borrow and use its forms, to accelerate growth, to contain and harvest?

How far is too far?

Glasshouse was thoughtful, deployed an excellent aesthetic and had a solid DIY feel. The presence of extra essays around the idea of glasshouses from other artists and the use of a couple of nicely chosen found items gave the exhibition an expansiveness, as if the artists were inviting the community not just to observe the ideas here, but potentially go a bit further in their own investigations and questionings.

Things spread out, seeds get planted and tendrils extend, which is sometimes just what art should do.

NOTES ON TOPPLED STATUES

I want to think here about the action of toppling statues.

I want to not just think about the one that recently tumbled with complete lack of ceremony in Franklin Square; I want to think about many statues and how they are removed, because they are, and how they are altered, because that happens with surprising frequency the world over. I want to think about how I feel about statues and how culture changes and who makes choices.

There was a significant wave of statue toppling and removal in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests after the murder by police of George Floyd. Statues of historical figures that were involved in slavery, or were Confederates in the US civil war, or who were racist, were toppled and vandalised. There were also a number that were pre-emptively removed and re-housed, in some cases this occurred due to campaigns that revealed the problematic nature of the people depicted.

There’s a lot of information available about statue-toppling as an act, and I’ve been sifting through it for a while now.

It’s in fact an ancient practice, so much so that there’s a word for it: iconoclasm. This comes from a social belief that it’s important to destroy or deface statues and images for political or religious reasons. People who support these varying practices are iconoclasts. Iconoclasts are people who challenge accepted beliefs or institutions.

Idea into practice.

This happened in Ancient Egypt, early Christians did it with Roman statues of gods, there were large riots and looting all over Europe during the Reformation – and we know this because there’s substantial historical record, even art. Drawings and paintings of people breaking, burning and smashing stuff. There was a lot of idol-smashing during the French revolution, and some people in the US tore down a statue of George III during the US revolution. They melted it down to make bullets.

The list is long: Statues of Saddam Hussein, statues of Stalin get pulled down. Christopher Colombus. Winston Churchill gets vandalised.

The Berlin Wall is torn down.

Things change.

Here, in what is now called Australia, statues of Captain Cook have been toppled or moved. One in Cairns, a massive hideous concrete thing, was legally removed after a successful campaign.

My point here is that this happens, and it always happens, and it’s a thing humans do. I’ve barely touched on how often it occurs. It happens mostly when there’s some sort of cultural shift; when how a culture considers something is changed somehow. This is because statues are symbolic; that’s the intention and that is how people understand them. Their function as symbolic objects is at the forefront of what they are; and how a culture understands them is going to change as culture changes. Moving them becomes important, and calls to remove them get louder, and they permeate the cultural zeitgeist. It’s never just one statue either; what my scant research has indicated is that this happens in waves, and it happens when a culture needs it to happen.

I don’t really want to compare Stalin to William Crowther, but statues of Stalin were removed as the countries they were in changed politically.

Last week I went and saw an exhibition that featured an image of a toppled statue. It’s tempting to say this work predicted the removal of the Crowther statue, but it didn’t. It’s more of a symbolic call for the removal of all statues of oppressive colonialist figures, and furthermore it is saying it will happen:

That it is inevitable.

This call is being made by so many groups, by so many people in Lutruwita, just as others call for the removal of other statues the world over.

So, to see this as exclusively about Crowther is somewhat blinkered. It doesn’t matter if Crowther did other stuff that was ‘good’ or something. The statue of him is a colonial symbol that says to First Nations people: we steal and mutilate your dead body, and we do it for science, because we know better than you. It says you are a specimen. You belong in a museum, your culture is extinct, you are not real, and we can tell you that.

It’s horrendous.

The Crowther Reinterpreted project made this plain. It did symbolic things, because that’s what art does, and it reminded us that the statue was 'art', and that it primarily worked as a symbol, and that symbol was offensive, that symbol was frightening, that symbol told every First Nations person they were not safe.

I’m not interested in arguments about Crowther 'the Man.' I’m not going to have a semantic debate where interpretations of digitised newspapers from Trove are thrown back and forth. All the work the City of Hobart and the artists did for Crowther Reinterpreted determined that the statue was not something the bulk of the populace of Nipaluna/Tasmania even wanted anymore. Or even knew what or who it was in the first place.

Of course there are comments about History, to which I say: removing statues is history in action.

This is cultural change as a symbolic act, and toppling a statue is as much a symbol of change as making an artwork that shows a toppled statue is.

Appealing against the removal of the Crowther statue was a ridiculous attempt to stand outside of the movement of history. Attempts to claim or quibble about the nature of Crowther as a person miss the mark: that's irrelevant.

Crowther’s statue was a symbol.

The time of that symbol is gone, and so it should be, for the representation it makes is a vile one. The moment of cultural shift is upon us. Had that been understood, had there been no appeal against its removal, the statue would not have been cut off and toppled down, because it would have been removed. I’m also willing to bet the people who made the appeal were just causing delay and irritation because they could. They knew the appeal would fail. Everyone did. Too much work had been done, and, in part, it was art that did the work.

People like Jeff Briscoe and Louise Elliot simply do not understand art.

Art is curious. It asks questions and it reflects what is there. Art doesn’t give people the idea to lop a statue off at the ankles. That idea has been around for thousands of years. It happens all over the world, it comes from a range of ideological perspectives and it will always happen, because we have done exactly this when change comes for thousands of years. The action is the tide. Stand in front of it. Try to hold it back. See how that goes.

The statue of Crowther could have been gently removed, but people who do not know or understand history[3] arrogantly felt the tide could be held back.

History tells us it cannot.

One way or another, that statue was going. This is history, because history is alive and always happening. Statues do not contain it. Only we do.

These words are dedicated to all the Tasmanian Aboriginal artists who patiently and gracefully educated me over years, making powerful artwork that meets violence with truth, with much respect going to Julie Gough and Fiona Hamilton.

Your pride and gentle strength humbles me.

[1] I had quite the time researching the essay, and it’s worth noting all the things I dropped out; one was the representation of plants as monstrous that occurs in cinema and speculative fiction. This is so profoundly fascinating that I want to use the idea somewhere, somehow, and I really want to dig into that weird horror sub-genre that depicts nature in revolt – largely because we’re seeing genuine incidents of that right now. The Orcas attacking boats incidents has a fictional antecedent in the film Orca, say. I suppose the manner in which art and life are simply not separate is of great interest, and that as someone who grew up with cyberpunk, HIV, the cold war and the rise of the internet, I was essentially promised a highly dystopian future by all the media I consumed, from Doctor Who to Bladerunner.

[2] More Richie Culver than Barbra Krueger but hey, I love a good art work that’s filching from design and graff; Reece has the wherewithal to do both, the cheeky devil.

[3] I’m wondering if I will get challenged here, because I’m really not a historian, but I’m reading history as an art critic does, because that is what I am. If you do not agree, that is your right, but don’t come at me with weaponised uncertainty please. We all know what that statue signified.