LIFE/CYCLE

What’s a collective noun for a group of older women?

You follow an artist in their career and you watch them develop, if they do.

Some do not. Some find something that works quite early on, and that’s sort of it. They find the tiny variations in one thing, and move there. This can be amazing, and it can be beautiful.

It’s also safe, and that’s fine too, but I am addicted to risk.

Artists that do what you do not expect them to do are where it’s at for me. I seek that stuff out, I want to know about it. I don’t think it’s better – art isn’t a contest. I just see, for myself, that life goes in stages, stages not marked out, that bleed and fray into one another, this loose thread becoming a whole new tapestry, and that change comes, and it’s terrifying and beautiful, and I think I can say I need to experience art that has beautiful terror and ecstatic growth and great, rippling change embedded in it.

I don’t think art changes the world by itself; but I do think art rings the time, that it notes that things are happening. It particularly does this when there’s resistance to what art is or says; but it can also be the moment when the artist changes, when the artist does something new.

Life/Cycle is a project created by Jane Longhurst. She didn’t make it on her own, but the impetus came from her. Jane is interesting as an artist, to say the least. I have to go back some years to when I saw her perform Grounded, a one-woman show about a drone pilot who kills targets remotely. Jane was electric in this, expertly directed by the great Annette Downs, and the play itself had something important to say. It was a success, and drew me back into having an interest in live theatre.

Theatre turns out to be a great place for crucial comment in the contemporary era; it’s a malleable medium that people can do adventurous and experimental things with. It’s also hard to get off the ground, and a costly medium to do with anything resembling professionalism.

Nonetheless, I kept seeing Jane Longhurst do interesting work[1]. The Green Room was a site-specific work that took place in a gunpowder magazine on Hobart’s Queen’s domain. Jane worked with sound artist Dylan Sheridan to create something more like performance art; it was also arresting, and more than that, unexpected.

What came to be called The Black Bag Trilogy turned up a few years later, beginning with a take on Beckett’s Happy Days. This is a bastard of a play – the central figure, Winnie, spends the first act buried up to her waist in a mound, then the second up to her neck. It’s a challenge, but it’s also a mistake to think of it in terms of athleticism – Beckett stuck Winnie in a mound for an actual reason, and smothering that with acting chops would deny the desired provocations found in a play where a woman is slowly being consumed by time. It’s a fine role for a woman who is, I might say indelicately, getting to middle age – and when it’s played by a woman who is getting to middle age, there is rich friction to be found. I liked that play a lot, and I saw Jane using her own truth and reality as a woman who has seen a bit of life to inhabit the part, and give it rich meaning. She had been good in the other things I mention, but this – this was different, and really did something potent. It also sent a signal that Jane was not afraid to interrogate herself as an artist as part of her creative approach. There’s a rawness implied that really made Happy Days powerful, and it was impressive the way the actor found personal truth in a character written in 1961

But then, there was the second part of the Black Bag.

This was Request Programme. This striking and challenging work had no dialogue. It was a hyper-realistic play about an isolated older woman, living in a flat, her life a cycle of repetition and nothingness, who listens to a radio where people ring in requests. This was an acting challenge, again, but it was also an intense one: for it to really have impact, Jane had to not act, but be totally real.

I felt that she did this with incredible, powerful understated passion, and managed to exude a contemporary cultural loneliness in an urban nightmare of Late Capitalism. Request Program was also about women, about older women, but it went further and was somehow more dreadful. The shattering, unavoidable bleakness was so real it was like being underwater.

Request Programme was certainly a play, but it was different to what I’d ever seen theatre be, and that was something. It was also quite a thing to see an actor I know is very good at speaking not doing so, and re-writing what acting can be.

It was clear as well that Jane is someone who relishes a challenge. This is how we arrived at the third black bag. Winnie had the bag in Happy Days; there was a bag in Request Programme. The Black Bag, invented by Becket for his play, had come to mean something to the artist; something about bleakness, isolation and the invisibility of older women in a youth obsessed culture.

None of us are getting any younger, and aging brings things that are useful and things that terrify.

Life / Cycle, the third instalment, of the Black Bag Trilogy, was very different in that it was devised by Jane Longhurst. She did a lot of work with a lot of people, and you cannot forget that theatre is a community that makes art together, but let’s stick with the idea that Jane is the core of the work for now. Sorry, all the other people who worked on this, and there were many, but there’s a point to be made here.

I really hope I’m not being ungentlemanly, but Jane is a woman who has been working for a while, who is a good actor, a really good actor, and who has nothing to prove there, who decides to re-invent herself as, I guess, a director, writer and deviser of live experimental theatre. This happens because it’s a totally logical step for the artist to take: to really use her chosen medium to actually say something, and that something comes from a desire (is that the right word? Need? Compulsion?) to make something that is about the process she has been through, but to remove from being “about her”

Jane is the material she works with, but it’s not about her; it’s about women and what happens to women. It’s not just about that, but that’s where Life/Cycle starts as a concept.

It must be noted that Jane Longhurst, gifted performer and actor, does not appear in Life/Cycle.

This was another big step, but it was the right one to make: it’s a good aesthetic decision, and I found it very potent that a performer who has established herself as being excellent at holding the stage as a solo performer eschews her most reliable ingredient for success. But at the same time, I expect nothing less: another barn-storming solo performance would have been good, possibly even astonishing, but it would also have been more of the same.

I just can’t see Jane falling for that. So, she does the harder thing.

Does it work?

Of course it does, and works because Jane did what good artists do, and re-invent, and that’s because she’s a good artist.

Life/Cycle was three tight acts with a short prologue and epilogue. It was staged in The Old Mercury Building, and thus supported by Detached Arts Organistation, and it was part of the 2025 Ten Days on the Island program. The space is not a theatre (indeed I think it was a former loading bay or something of that ilk) so it had to be constructed from the ground up, and the staging made use of the industrial history of the building without allowing it to overwhelm the work, which was impressive in itself. It’s something of a comment around the actual state of live performance in Lutruwita right now that this was the best option for Life/Cycle; spaces that can host experimental work of this nature seem few.

What was Life/Cycle?

This is hard to say, interestingly.

It had elements and ideas somewhat gleaned from the two earlier works that made up the Black Bag Trilogy. There was something that I could call dance, but I could also call it ritualised physical theatre too, and it was possibly more that, than dance. There were very powerful visual elements. There were strong, strident sound elements.

There were lots of performers, almost all of them women, and yes, again, middle-aged women[2].

I really hope I’m not labouring that point but it seemed to me to be astonishingly important.

We have, in our culture, a real focus on youth, and in particular in any kind of performing arts, younger women, and there’s something already problematic about that. We associate youth with energy, with beauty, but also with naivety, lack of experience, and vulnerability. In opposition, as women become older, they are relegated to social and cultural roles where they become invisible, are deemed to have become perhaps useless by society-at-large, and are sort of dismissed as artists. The very existence of Life/Cycle doesn’t just question this state of affairs, it really strongly says no, this is not the case it proves it in multiple ways.

What do we call a group of older women?

The available collective nouns are far from flattering, which is also telling, and un-nuanced.

I lean towards some kind of magisterial allusion to witchery and wisdom, though, and there is a reason for this that relates back to my question about Life/Cycle – what is it?

I saw this work, after much consideration, as a performance ritual. I think it came from the world of theatre, and still has roots there, but I also think there’s a notable shift. There are signs of this in the staging; there’s a bright, cloyingly bright set, that is the location of much of the action, but it is also not: there are plenty of moments through the work where the set was not stuck to, and the wider environs of the room where used. There was no requirement to suspend disbelief – you were not watching people ‘act’. You were watching people do things in a space as part of something like an evocation of idea and intent.

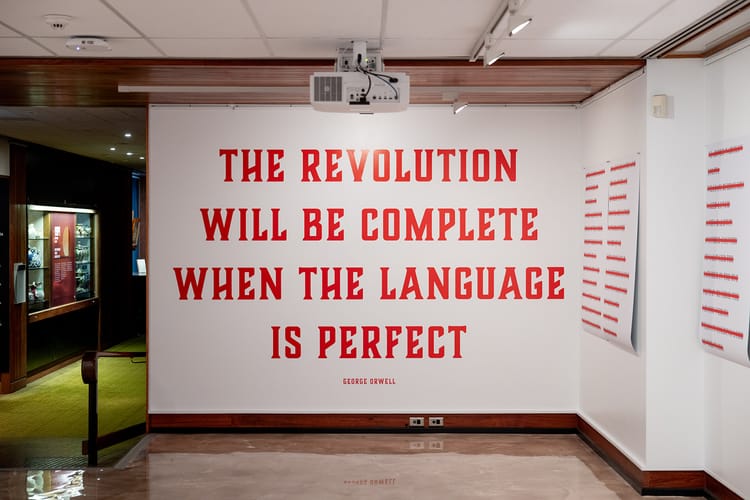

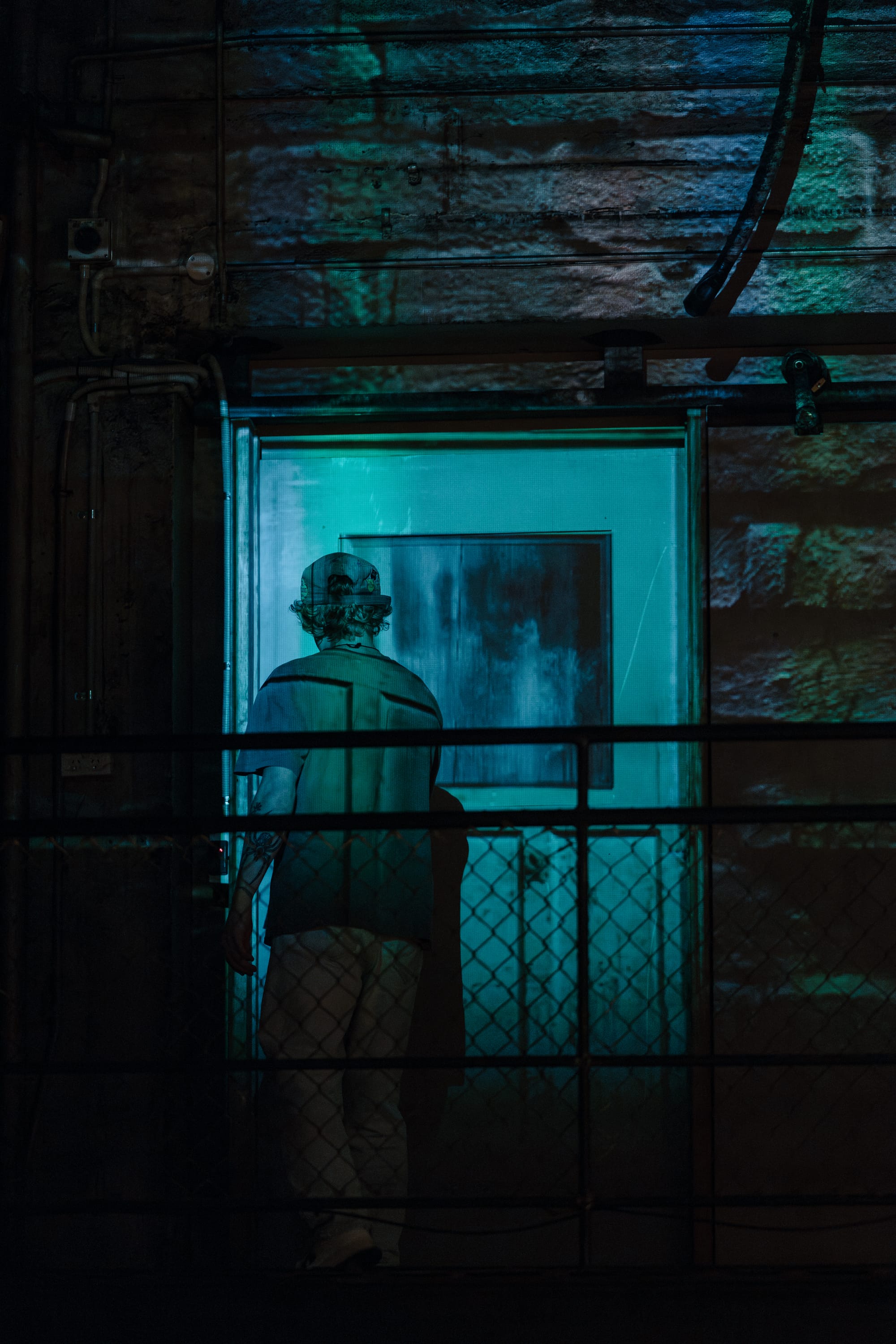

There was the Foley Artist. The Foley Artist was one of three males in the show, and the foley artist was very present, but in the background, up on a balcony, obscured under a hat that suggested the tropes of Film Noir[3]. There were so many things this male presence could be, but let’s just say for now that he was part of an effort to show the mechanics in action, to let everyone into the notion that this was a performance.

This tactic is fascinating to me. I find it makes the performance more real. There is no effort being made to convince with acting chops that it’s a real character one is seeing: instead, we know these are performers, presenting us with images and moments, that we will have to work to interpret. It feels like an invitation to dialogue, to consider what is being shown – there’s no disbelief to suspend.

We were even told what we were watching by a handy projection: Prologue. Act One. And so on. They wanted us to know, and so we did, and it was particularly important that this happened.

The Black Bag was there, but now, it was a centrepiece. It had just sort of been there, carrying things, in the prior works, but here it was over someone’s head, a mask, a blindfold, and a game was being played with the bag: Marco? Says one character. Polo! Says the other ducking and weaving, never still, the other, blinded by the bag, flailing against the lack of light, as the playmate remains elusive. It’s all on the lovely bright yellow set, the lovely domestic space, the safe space to play in that has edges you do not go past, despite it being really a little island in the dark, and not even being real, but it’s great place to play Marco Polo until the person you seek in the dark drifts off and it’s not a game.

It wasn’t a game at all.

Life/cycle was generally quite frantic, even when still. The narrative was built of expressive images created in performance; we meet various performers who seem deeply symbolic: a younger boy, trying to dance, who is intruded on by a still young but a bit older male – who is terrifying. Almost feral in nature, this more adult male moves sharply and abruptly, taking risky jumps, climbing, hanging, throwing his body everywhere, seemingly explosive and violent. His very presence felt dangerous – or at least potentially so, and unfortunately, that’s men for you right now. We know there to be a terrifying problem with male violence toward women, we are starting to understand the existence of very problematic people attempting to steer young men toward truly horrific behavior towards women and how aspects of internet culture are facilitating this; we know not enough is being done, and that women are being murdered.

If we dare to look, we also know this is a part of something far larger and darker rolling out across our world, and that it is no mistake that accused sex trafficker Andrew Tate was repatriated from Romania after high-ranking Trump Administration officials took an interest in his case[4].

I watched as the terrifying male character taught the younger boy to dance and move and then led him to a very dangerous edge, where the lights came down before he could actually jump off. I was disturbed, and no doubt I was meant to be.

It’s clear that if you want to talk about what is happening to women, you need to talk about what is happening to men; to boys, to the world.

I think this is part of what Life/Cycle had to ask us about as an audience, but I am getting ahead of myself here.

There were other moments and scenes: women as domestic goddess clones making a home that was perfect, at least on a surface level, only to see it broken and shattered. An astonishing ritualised set piece constructed that domestic fantasy space, women in old style dresses gliding and unreal, beautiful and dedicated. This is something I would have once referred to as artificial and made some allusion to The Stepford Wives, that deeply strange and utterly horrible fable of carnivorous misogyny. However, that’s too easy; I think it’s completely possible to be a domestic goddess, and be a feminist, and that actually, I don’t get to dictate what a woman is or should be. Life/Cycle celebrates women who run homes and raise children whilst being critical of the patriarchal constraints placed around those roles: Women make the home, and they clean up the damage when careless men destroy it too. It’s a fine point, but something Life/Cycle was really doing was asking about accepted structures and narratives, and who actually decides what those are; women who run homes and raise children do a tremendous amount of unpaid labor, and that actually needs celebrating, needs acknowledging, rather than condemning. I should point out that I am not elevating a particular role for women here – rather I felt the presentation of a series of astonishing, powerful domestic high priestesses was a complex notion that contained a number of potential interpretations, and intentionally did so; the artificial perfection was later shattered, destroyed and collapsed in a majestic live special effect that was quite unnerving as we saw a table’s contents unfurl onto the floor by itself, occult and disturbing.

Things fall apart.

Image after image is shown, and the work is about an hour in length, and it has excellent pace, really whipping past, so much is seen, shown and I have to say this: it was all very damn good. But one moment really, really seized my mind.

The most intense image we were presented with came with a much barer, more raw moment. The large group of women who had been so many things by that stage of the performance appeared in contemporary, ordinary, even daggy clothing. I recognised this attire: it’s my works clothes. I sit in them right now, the comfortable and practical clothing necessary for juggling writing with tagging out to make lunches and hang stuff on the clothesline.

The large group of women were holding pots and pans and beating them rhythmically, and this was an amazing moment in a series of amazing moments. I was hit by this sound, by how many women were making it, and by how defiant and transformative it seemed. You will not ignore this, you will not ignore us; you will not ignore this art (making music is art. If all you have to make art with is banging a pot, and you do it, and you commit to it, it’s really potent, wild, rich art), and it connected with. It felt like a central moment to me; it felt like a rich celebration of the power of a collective, a collective of women.

Which I could suggest was what Life/Cycle was as a whole.

In a show with a great many revelations and observations about the spaces women are in right now, I think the most intense and underlying revelations came from the central artist. This is why I had to create a context for the work out of prior work, because what I have come to understand this work as, now, after deliberating and following side lines (I tracked down and watched The Stepford Wives, as an instance of this), is pretty much where I started : I think the project began with Jane looking at what she could do as a middle aged woman actor, and then discovering something in that process, and undergoing what looks to me like an astonishing personal transformation. I think she started, with Beckett, and with her own challenges. She meets that challenge, with Beckett, and it’s not what she’s actually looking for, because it begins a much larger investigation.

Request Programme was another challenge, and it’s amazing, but no. The itch is not scratched, and that’s because, ultimately, I am daring to suggest, that the project became not about finding something for herself to do as an artist, but finding a way to speak for women she shares her experience with. The Black Bag shifted and became a search: Marco? Polo!

The trilogy looks at the situation Jane is in, and the situation that women like her are in, and arrives at what can we do?

How do we keep the lights on?

There was a very notable framing device that punctuates each act: a single performer mounts a stationary bicycle, pedals frantically, creates energy, and the lights come on, the performance continues, the action starts. A different person does this, and it’s a glorious metaphor (really; I loved this, it was just elegant, but it talked about bodies and sustainability and climate breakdown and where change comes from – a superb thing), and people get tired and someone else takes over, and we keep the lights on, and it’s a cycle – it is literally a cycle.

Which is funny, but also, as I say, fabulous.

It's like the artist decides to be become more, and to do something more, which is make new art. Art does not change the world but it does open eyes, and does articulate things, and it can make us think, and we need to think, and we need to talk to each other, because our culture is in fragments: There’s no theatre company in Nipaluna now, and that’s a terrible state of affairs.

It's like the artist, in making a work, decides to involve other people, and that makes a more powerful work that exemplifies the power of a collective, demonstrates what a collective of older women can do, and this is why I didn’t like any of the available collective nouns, and why I now want to call a group of middle aged women a Collective (the answer is, as it so often is, in the question. Look. See. Ask Questions. Marco?).

Life/Cycle had a tonne of stuff, it looked beautiful, it was very clever, it was far from what I expected, but really, the only thing I expected was that it would be fucking amazing, which it was. It exposed challenges faced by women in the world right now; it gestured toward violence, fascism, surveillance and danger, and it produced as well a realistic solution: get together, find your people, find your strength as a group, and see what you can do. It suggested we look to the resources we have, and that all the skills women have already are useful and are powerful: could there be anything more important than nurturing and creating safety in a frightening world?

And this majestic piece of art was the thing it showed. It was the collective in action, it was that thing it was talking about.

That’s what really blew me away, and why I was almost moved to tears by this show, because yeah, it was just art, I know, but it was also the living embodiment of the effort it described, and it was, thusly, filled, to the brim, overwhelmingly, generously, with hope.

And if you had forgotten that hope exists, it does, and sometimes art can remind you of that.

[1] I should point out that Jane did a lot more work than what I mention here; I have cherry picked material that marks out what I saw as a kind of trajectory.

[2] I’m sorry to relegate this to a footnote, but MADE – Mature Artists Dance Experience – were important collaborators, and I have to note with great joy that working with a company of older/mature women was such a terrific bonus undertone for a show like this.

[3] I really like Film Noir, especially the classic Forties period in Hollywood. This is a huge topic, but one thing is relevant here: Noir is often an examination of male sexuality and orientation, and it features some of the strongest female parts ever created for film. It needs noting that these strong women are ‘bad’ or ‘evil’, and often come to awful fates, but they have agency and understand how to survive in a dangerous, patriarchal world.

[4] If you want details about this, there’s an article you can read